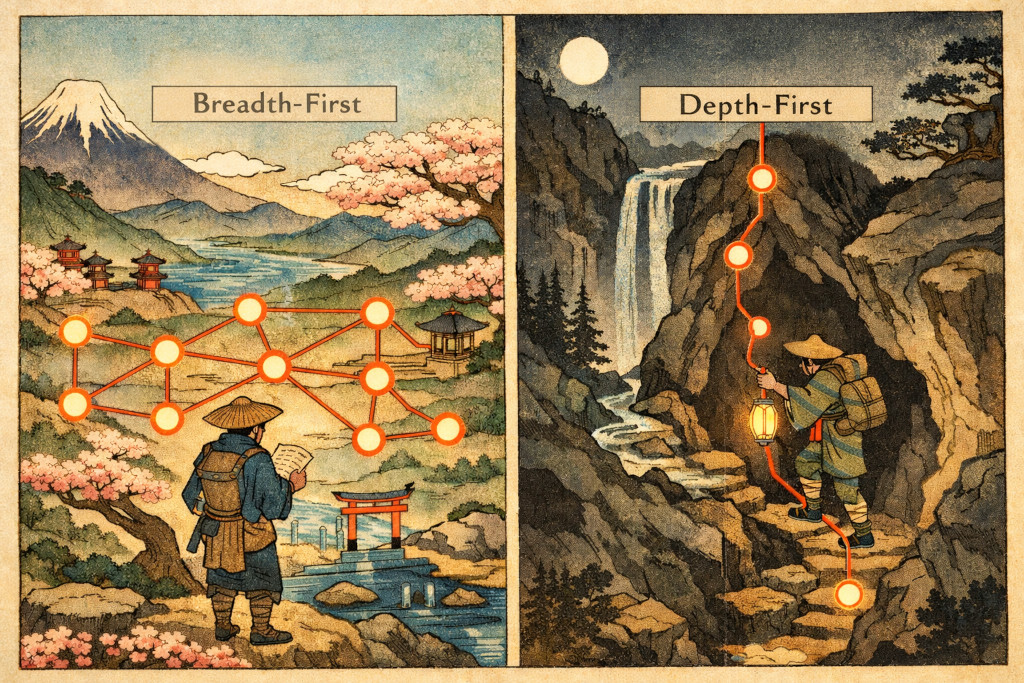

LLMs think breadth-first, humans think depth-first

I've formulated my main conceptual issue with LLMs at this point, based on my personal experience.

The problem is less noticeable in chats — it gets smoothed out by the continuous interaction with a human who steers and corrects the LLM.

However, it becomes much more noticeable during vibe coding, or when you ask an LLM something that calls for a large abstract answer.

Donna — predictability and controllability for your agents

Looking for early adopters for my agent utility.

I named the tool Donna — https://github.com/Tiendil/donna

With it, your agents will generate state machines while executing state machines created by other state machines.

Donna allows agents to perform hundreds of sequential operations without deviating from the specified execution flow. Branching, loops, nested calls, recursion — all possible.

Most other tools just send meta-instructions to agents and hope they won't make mistakes. Of course, agents make mistakes: they mix up steps, skip operations, misinterpret instructions. Donna truly executes state machines: it maintains state and a call stack, controls an execution flow. Agents only execute specific commands from Donna.

However, Donna is not an orchestrator, but just a utility, so it can be used anywhere, no API keys, passwords, etc. needed.

The core idea:

- Most high-level work is more algorithmic than it may seem at first glance.

- Most low-level work is less algorithmic than it may seem at first glance.

Pricing model at the start of Feeds Fun monetization

Right after I started working on the pricing for Feeds Fun users, I realized I should do it in a blog post: it's almost the same amount of work, it's the ideologically right thing to do, and it should be interesting. Anyway, I was going to write an RFC — the question is purely about publicity. I'm also taking the opportunity to conduct a retrospective on the project for myself.

What is Feeds Fun

Feeds Fun is my news reader that uses LLM to tag each news item so users can create rules like elon-musk + mars => -100, nasa + mars => +100. That effectively allows filtering the news stream, cutting it down by 80-90% (my personal experience) — no black-box "personalization" algorithms like in Google or Facebook; everything is transparent and under your control.

So, meet a free-form essay on monetization of a B2C SaaS dependent on LLM — couldn't be more relevant :-D

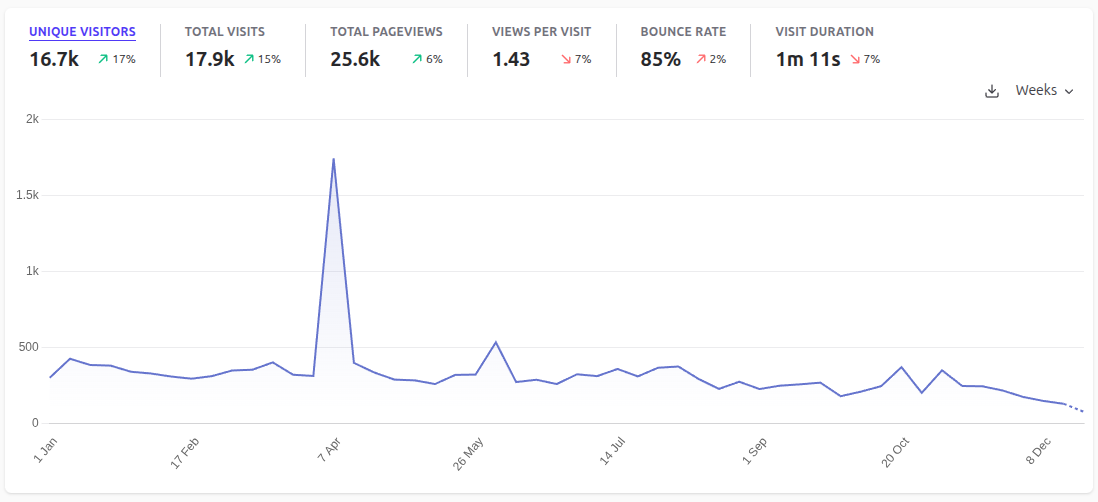

Results of 2025 for me and my blog

Blog metrics for 2025.

The New Year is near, so it's time to sum up the results of the year. Let me tell you what I was doing in 2025, how my plans for the past year went, and what my plans are for the coming year.

LLM agents are still unfit for real-world tasks

AI agents show their work to a programmer (c) ChatGPT & Hieronymus Bosch.

This week, I tested LLMs on real tasks from my day-to-day programming. Again.