Vantage on management: Hypothesis testing loop ru en

The feedback loop (c) Hieronymus Bosch and ChatGPT

We generally assume that if our product has such and such attributes, then people will be willing to pay such and such money for it.

Sometimes we make assumptions explicitly:

If we paint the sign red and light it up, the number of evening visitors to our restaurant will increase by 10%.

sometimes we do it implicitly:

I'll build the coolest theme park on the Moon with blackjack and AI.

but I'd venture that one can't avoid assumptions altogether.

These assumptions we call hypotheses.

Based on these hypotheses, we modify the product, measure the results, and then decide which hypotheses are right and which are not. The correct hypotheses remain in our worldview and product; we abandon the incorrect ones. After that, we form new hypotheses and repeat the cycle.

This cycle runs perpetually while the product exists and is a special case of the feedback loop.

There's a wealth of literature on this cycle, its implementation, and its various nuances. The best practices are packaged into kits for every taste [ru]: from intricate system engineering to Lean Startup and Agile. The cycle itself is known by dozens of acronyms: PDCA, OODA, DMAIC, 8D — too many to count — every self-respecting guru-consultant with a book under their belt adds a new one.

Kicking off the feedback loop is absolutely crucial — without it, the product is toast, like any other endeavor.

However, it's not enough just to launch the loop — what you do within it is just as important.

The latter isn't covered as thoroughly in the literature as it should be. One thing is to look at simplified cases in books. Another is to steer a real-world product in real-time, dealing with all its complexity, opacity, confusion, delays, data gaps, and so on.

That's why, in this long essay, I'll try to delve deeper into one specific stage of the feedback loop that's often unjustly overlooked — hypothesis synthesis.

Yet another feedback loop description

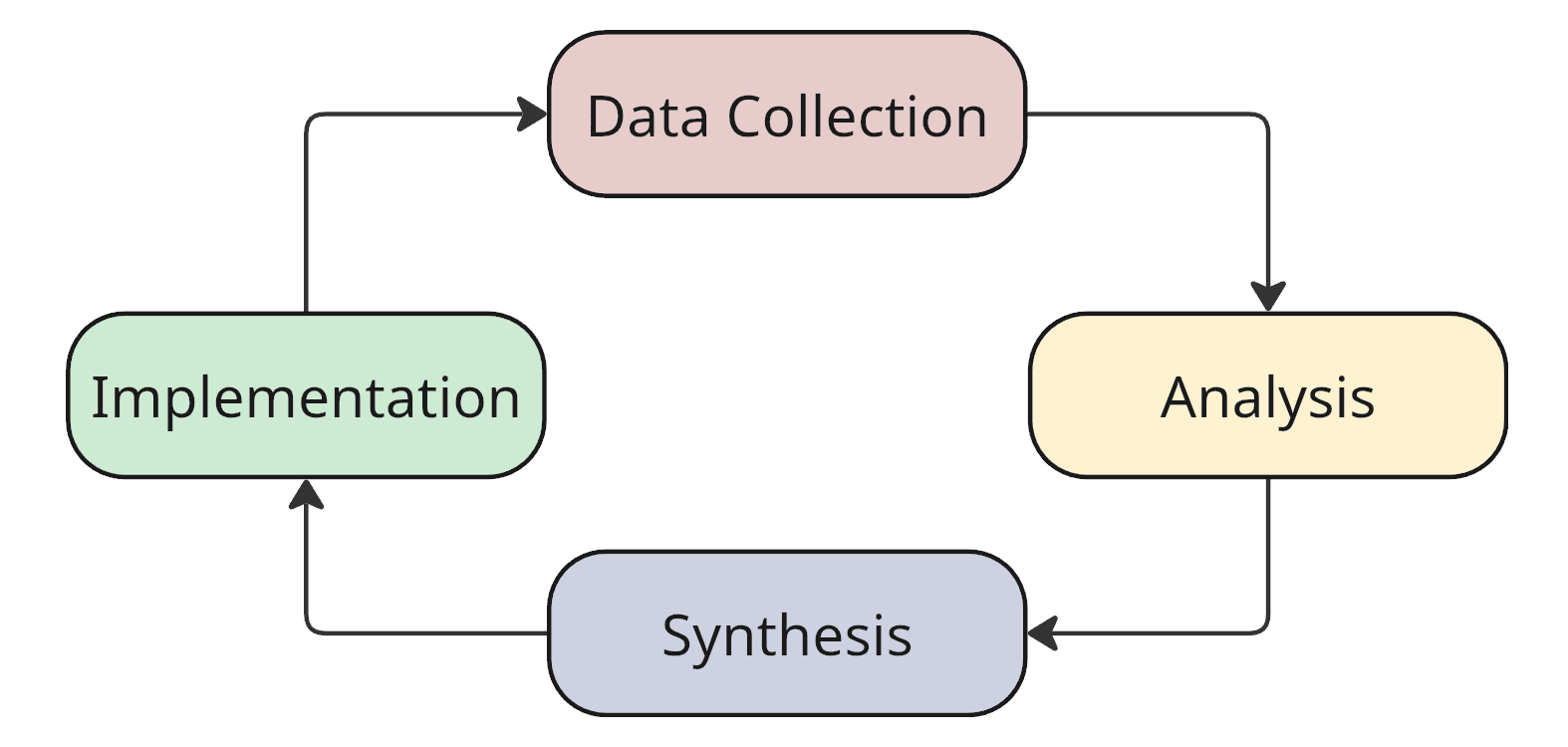

To not fall behind the trends and be on the same page with you, here's my take on the cycle:

- Data collection — we gather data about the current state of the system and its environment.

- Analysis — we clean up the data: structure it, identify patterns, group it — reveal the orthogonal properties of the system that we can operate with in the next stage.

- Synthesis — we form hypotheses based on the identified properties.

- Implementation — we make changes to the system based on the hypotheses.

Simple feedback loop

The data collection and analysis stages are well-studied and documented, especially for startups.

The implementation stage is largely a (socio)engineering challenge. Once you've determined exactly what needs to be done or achieved, there's usually no more conceptual complexity — only technical one: how to implement it, how to launch it, how to evaluate the results within the available resources.

However, when it comes to synthesis, things get trickier. Often, synthesis is assumed obvious: you see the data after analysis, and hypotheses just pop into your head. There's literature on synthesis too, but it seems that fewer people are familiar with it compared to other stages.

Hypothesis synthesis

I won't argue that people have thoughts in their heads — that's a well-known fact. However, spontaneous ideas are not the best we can use. Anyone who has worked in front-line positions where ideas come from above will understand what I mean :-)

A diverse range of practical approaches has been developed for hypothesis synthesis: from a predefined list of heuristics in TRIZ to morphological analysis and optimizations on it. I even once created a tool for morphological analysis [ru].

A comparative analysis of these approaches would make an excellent essay topic — but let's save that for another time.

In this text, I'll try to approach hypothesis synthesis not from the "bottom up" — from specific practices, but from the "top down" — from the general attributes of products and hypotheses. We'll discuss which product attributes are most suitable for hypothesis generation and what general approaches to hypothesis search exist.

By the end, we'll formulate a hypothesis-search algorithm that should significantly improve the quality of product hypotheses — and, by extension, the product itself.

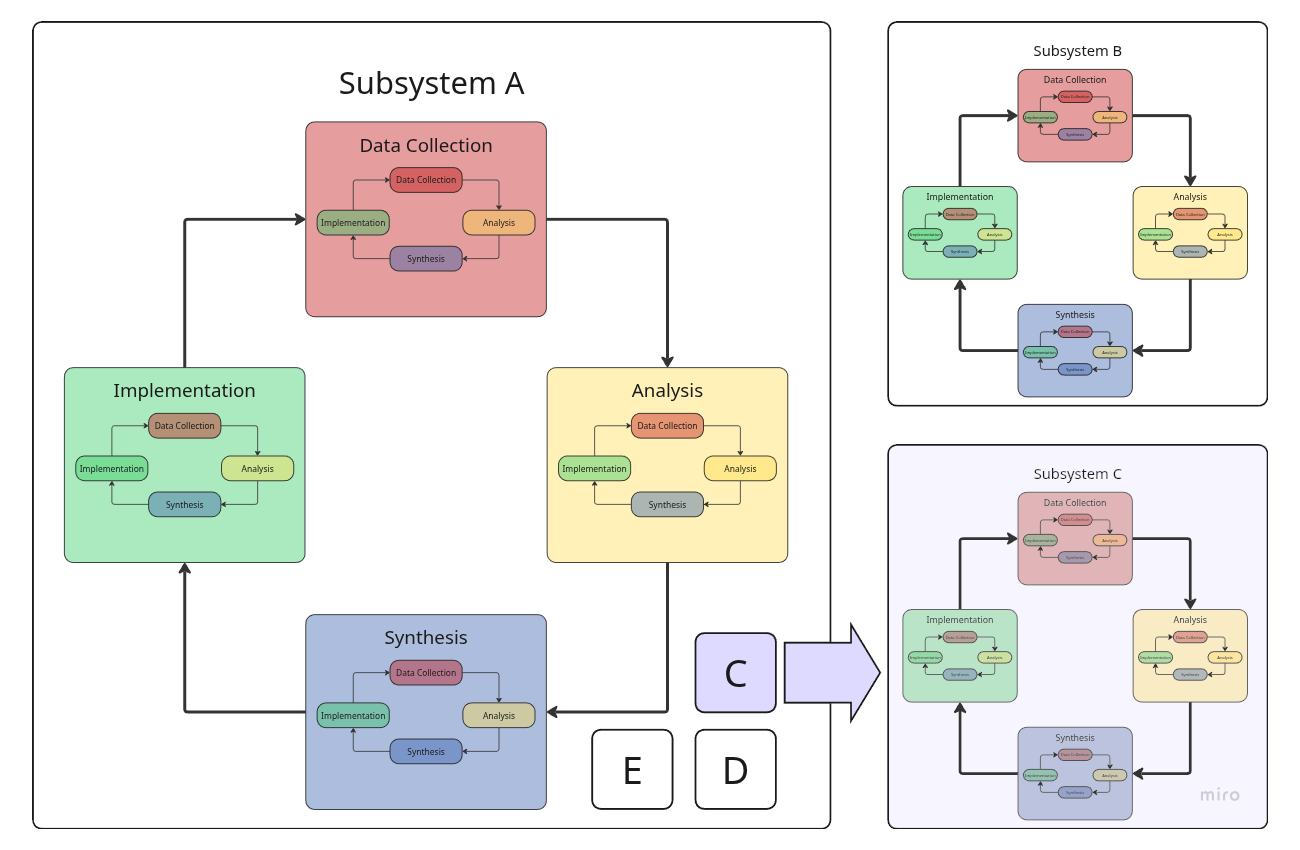

Nested systems and feedback loops

Formally speaking, any complex system, including any product, is a collection of nested (sub)systems where each can have its own feedback loop. Moreover, each stage of the loop can contain a similar "child" loop focused on optimizing a specific stage of the parent loop.

For example:

- The marketing department can research advertising placement approaches.

- The development team can experiment with different technologies.

- The market data collection stage can be optimized by testing hypotheses about the best sources of information.

Как всё работает в реальности

I'll set those nuances aside and talk about the product as a consolidated system with a single feedback loop, for two reasons.

First, it will be simpler and clearer. Excessive details would complicate the text without adding new information.

Second, there's a fundamental distinction between the environment in which the whole product exists and the environment in which its subsystems exist. The product's environment is the real world — we don't control it and understand it poorly. The subsystem's environment is our company's environment — we control it (!) and understand it much better.

That's why formulating hypotheses about the end product is far more challenging than doing so for its subsystems. This text is devoted to that very challenge.

Third, we should steer the end product itself, not its components. We partially discussed this in the previous post and will continue the discussion here.

We draw hypotheses from models

Each of us carries internal pictures of how the world and everything in it works. We call these pictures mental models [ru].

We can apply these models to different situations and see "what if":

- If I cross the street on a red traffic light, a car will hit me.

- If I cross the street on a red traffic light in the forest on Christmas Eve, I probably won't get hit, as there won't be any cars.

If you think you're not using mental models, it only seems that way. Even intuition just taps into hidden models of reality deep within our brains that we're not aware of.

Models may not only be mental:

- Spreadsheets — for quantitative metrics — calculate EBITDA, analyze sales funnels, etc.

- Text documents, mind maps, etc. — for things that are hard to express in numbers.

- Sophisticated algorithmic tools — for cases demanding special accuracy or insight.

- Reports from the authoritative sources — when we trust others more than ourselves.

- …

Countless possible variations exist. For the purposes of this essay, it doesn't matter which models you use (there are more than one, right?) — what matters is how you use them.

We can test how a product model behaves when we tweak the product's attributes in it. If the resulting model's behavior intrigues us, we have found a hypothesis: "With such changes to the product attributes, the product will behave in such a way." We can then try applying it to reality and see what happens.

The bravest among us, of course, don't bother testing models — they change the real product — feedback is much faster, after all :-) But I'd still recommend leaning on one of humanity's greatest achievements — common sense.

How detailed should a hypothesis be?

Let's be honest, most people rarely formulate hypotheses in any explicit way. More often, a hypothesis sounds like this:

Something in the product will grow if we do something unnecessary.

or

I swear on my life — every client wants this, so there's no need even to ask them.

Often, it's hard to obtain even a well-defined qualitative formulation such as

We'll increase user retention if we implement feature X.

Hypotheses with clear numerical predictions are even rarer. Most people don't see the point of making them; some don't believe it's even possible.

At the same time, formulating a hypothesis with maximum thoroughness before implementing changes and measuring results is, sorry for the tautology, a maximally necessary action.

First, this requirement stems from Popper's falsifiability criteria — one of the fundamental concepts on which we've built science for the last 100 years. We build engineering and business on it, too, but not everyone notices this. By the way, I hope to dedicate one of the future posts to the topic of the similarity between science and software engineering.

The approach of "Let's do it without a prediction, then look at the results and draw conclusions" systematically fails. It leads to incorrect long-term conclusions and loss of significant information. This approach is so harmful that scientists have even coined a special term for it — HARKing — Hypothesizing After the Results are Known — to shame those who use it.

Second, the more thoroughly you formulate a hypothesis, the more you'll learn after validating it.

Of course, there's no guaranteed effective way to extract precise predictions from models, especially numerical predictions from our heads. After all, models are simplifications of reality, hence the loss of accuracy. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't try. The more detailed (and justified) our prediction is, the more accurately and thoroughly we can assess its error, and the better we can adjust our models after validating this prediction.

Third, quantitative statements are useful for comparing hypotheses. And without comparison, how do we choose what to focus on first?

Hypothesis search space

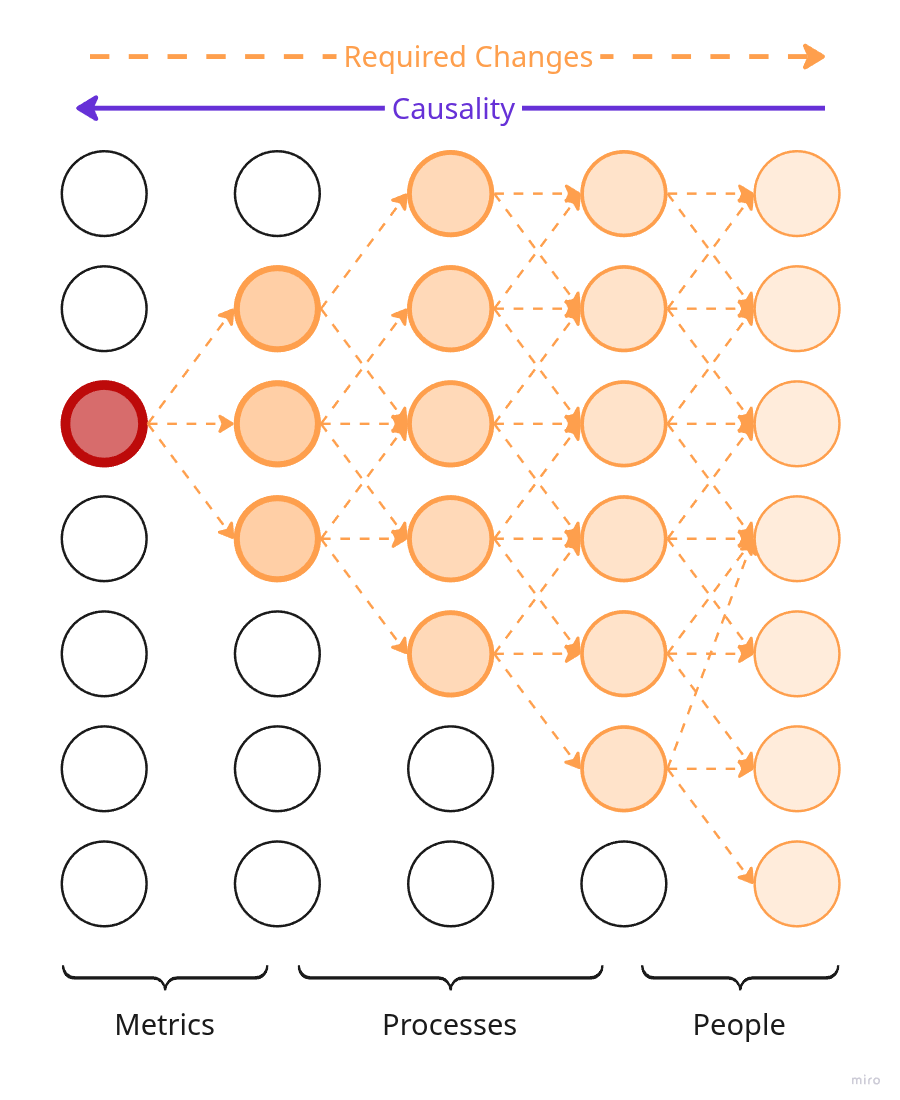

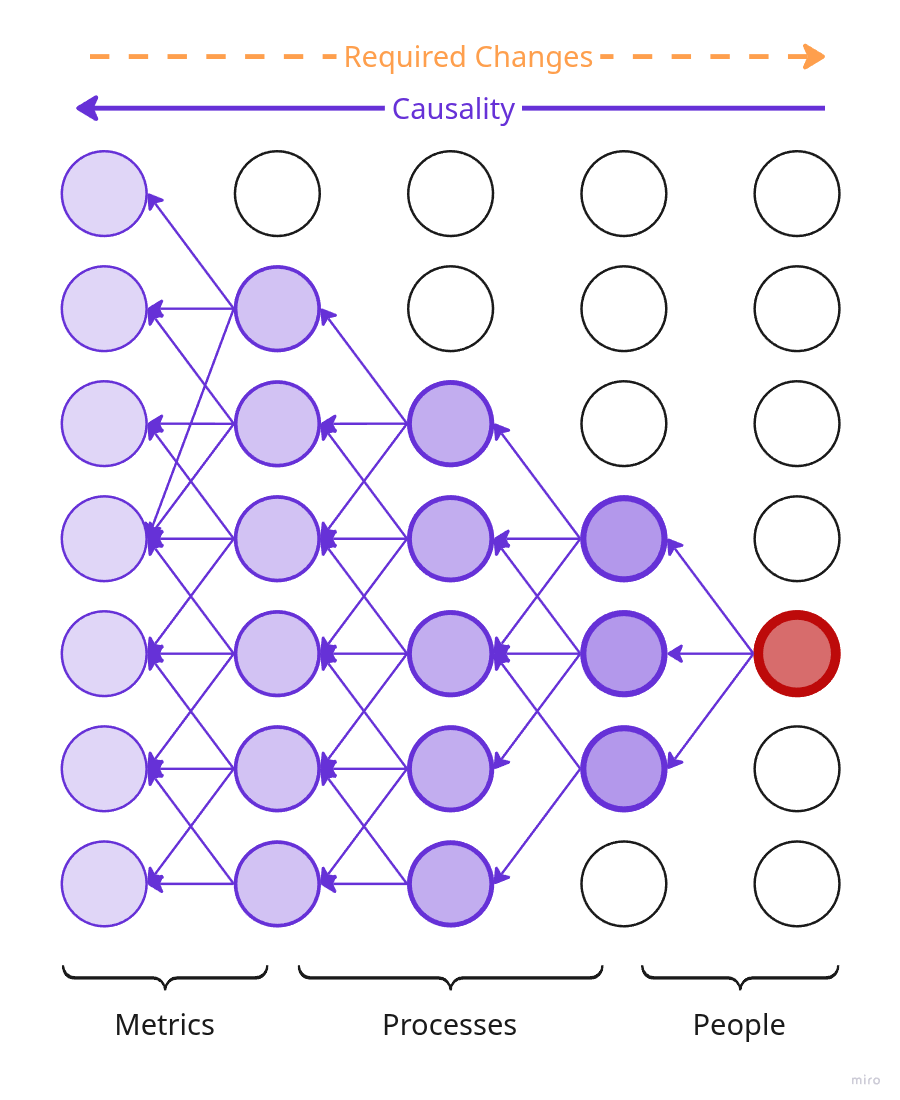

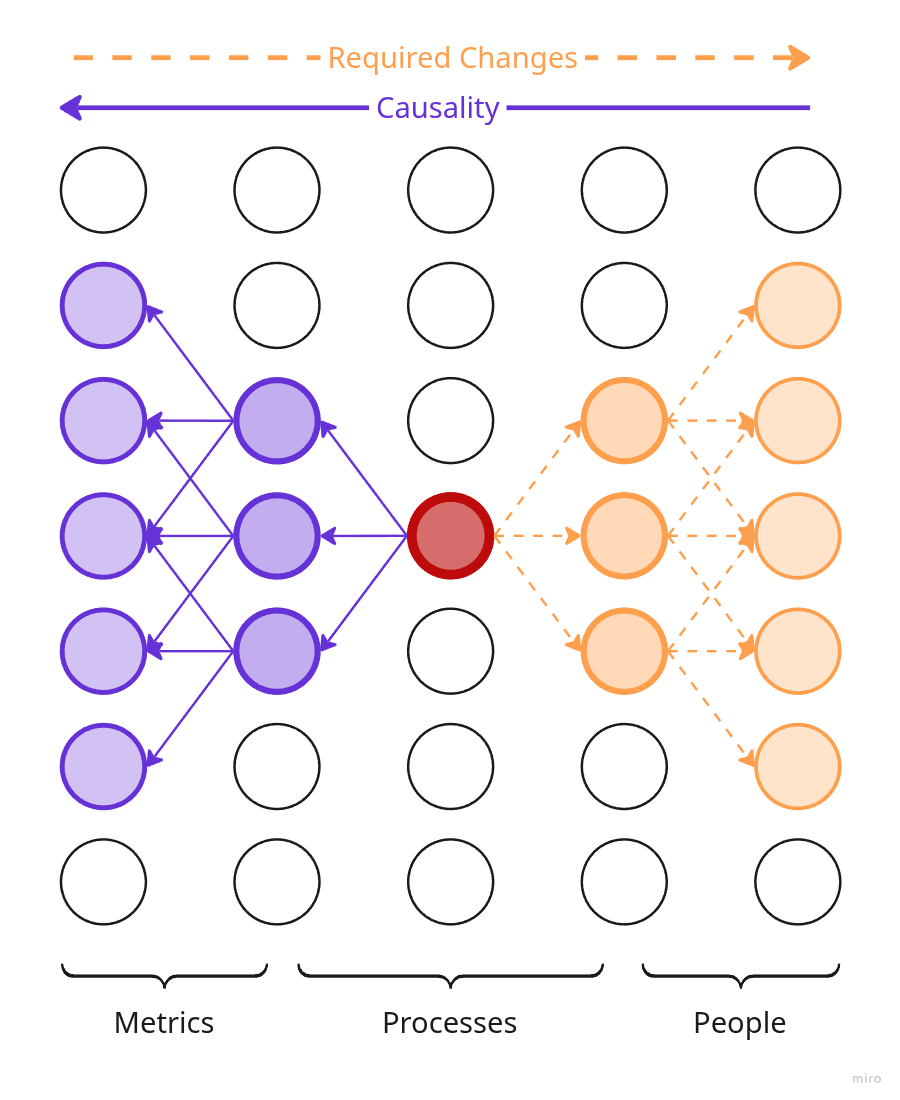

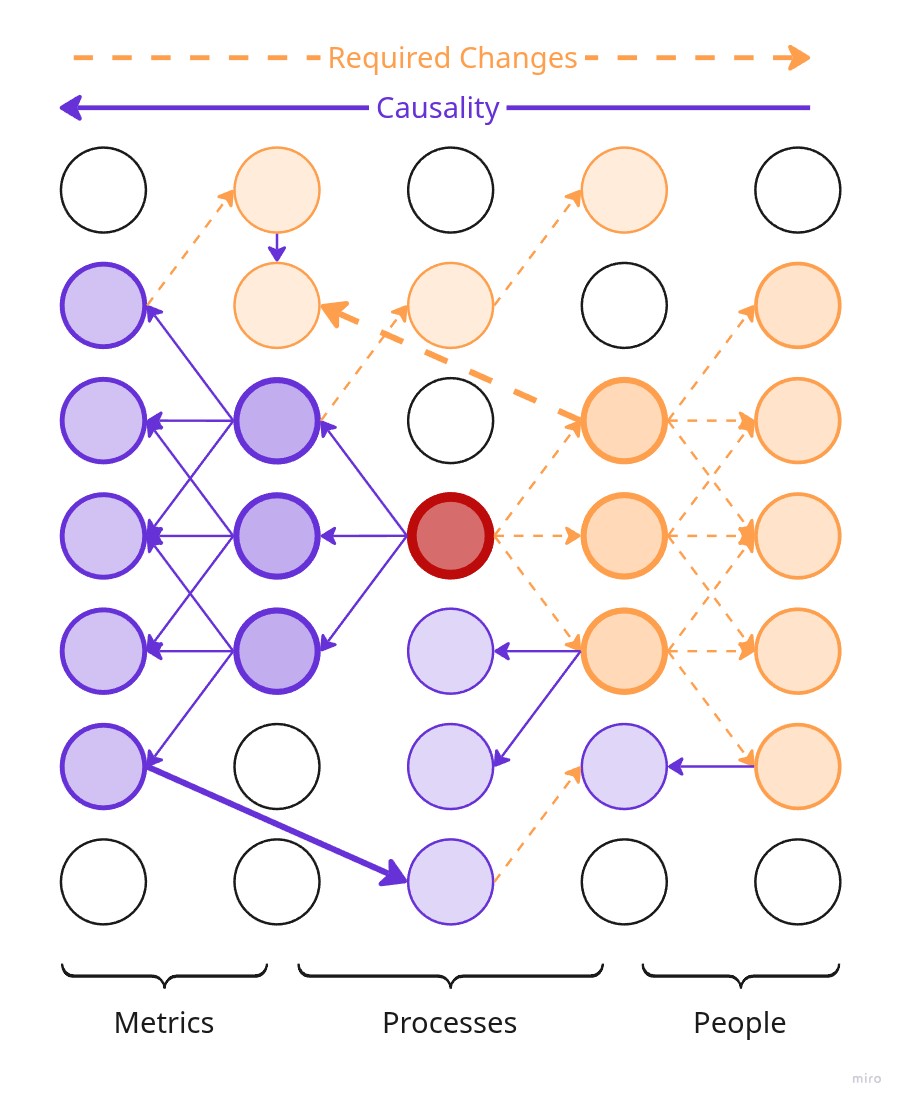

Regardless of its form, your product model is a network of cause-and-effect relationships that describes what affects what. Each node in this network is a property of the product or of its subsystem. Remember when we looked at the product from different points of view, we discussed that a product is not just what the user sees, but also the team, processes, side artifacts — everything that participates in delivering the desired outcome to the user.

If we change a property of one of the nodes (a product attribute), the changes will start propagating through the network in two directions:

- Forward through the chain of causality: what consequences will the change lead to — which other nodes will change and how.

- Backward through the chain of causality: which other nodes do we need to change to achieve a change in this node.

We can experiment with any node in the network, even multiple nodes at once. The pattern of change propagation will depend on which node you alter.

Simplified illustration of a product causality network.

In reality, of course, everything is much more complicated: a lot of reverse and bidirectional links, many more types of nodes, and generally no idea what's going on — about like in the fourth picture.

For example:

- If we want to change a downstream product attribute, like release frequency, we need to modify the components it depends on: workflows, team, maybe technologies. At the end, changing one downstream attribute may require changes across nodes in the causal chain that lie upstream of it.

- If we plan to fire a team member, the changes triggered by this will propagate forward through the causal chains and may affect numerous downstream product attributes at once.

- We can also change something in the middle of the network, like a specific workflow. In this case, the changes and required changes will start propagating in both directions. Since the distance to both upstream and downstream nodes is shorter, both "wings" of the changes will be smaller.

Downstream and upstream attributes

For convenience, I'll refer to certain product properties as "downstream" and "upstream". These terms should be understood specifically in the context of a causal network:

- downstream attributes — these are properties/components that are more a consequence of changes in other nodes of the network than a cause of changes in them. For example, release frequency is a consequence of the work of the team, processes, technologies, and so on, but it has less influence on the internal state of the product.

- upstream attributes — these are properties/components that are more a cause of changes in other nodes of the network than a consequence of changes in them. For example, specific team members usually influence a large number of downstream product attributes but are not influenced by them.

Since the product is a complex chaotic system, I won't overly formalize these concepts; for instance, I won't claim that downstream attributes should not affect anything at all. For the purposes of this essay, the above fuzzy definition is sufficient.

The more wisely we choose the nodes for our experiments with product models, the better our hypotheses will be, the faster and more effectively we'll change the product, and the more successful it will be.

This naturally raises a reasonable question: what's the best strategy for hypothesis discovery?

Trivial strategies for hypothesis search

- Brute force — we methodically check what happens if we change each possible node in the product model.

- Random search — we try to change random model nodes, hoping for a lucky hit.

- Using

intuitionexperience — almost like random search, but we strive to use our brains to avoid wasting time on completely meaningless options.

Obviously, brute force and random search are not the most effective strategies, as product development is a complex endeavor:

- Brute force will take too long, as the number of possible changes is enormous.

- Random search will be ineffective, as the number of potential negative and neutral changes is orders of magnitude greater than the number of positive ones. Just like in biology.

I've got nothing against intuition or experience — use them myself, and they even work sometimes :-) But they do come with a few problems:

- Not everyone has them.

- The area of their positive application is usually narrower than it seems. You may have experience in one or two very specific areas, but it's unlikely that you'll have sufficient expertise in all the areas that are significant for the product.

Experience and intuition work well for "basic" changes like "any seasoned specialist in X knows you should do Y if Z". Following such hypotheses can help you build an average product, maybe slightly above average, but you'll miss out on numerous more effective local improvements — they would slip through the wide mesh of the intuition-and-experience sieve.

Are there better strategies, more effective ones?

Yes, there are. The simplest thing we can do is narrow down the search area of potential hypotheses. To do this, let's think about what kind of hypotheses would be more convenient to steer the product. I've already touched on this topic in the previous post.

Heuristics for useful product hypotheses

At its core, a hypothesis is a statement like: "If we pull levers X, Y, and Z, then changes A, B, C, D, E will happen in the product."

It's clear that some levers are easier to work with than others. That means we can narrow the hypothesis search area to only include hypotheses with convenient levers.

To achieve this, let's use a few heuristics that I hope are obvious-enough :-)

The more levers we need to move simultaneously, the harder it is to steer. Therefore, ideally, hypotheses should be about influencing one attribute/component at a time.

The downstream attributes often matter more to us than others. After all, usually, the whole product development is about achieving specific downstream attributes like sizable revenue.

"Downstream" attributes vs "external" attributes

Besides the downstream and upstream attributes, if we look at the product as a whole, we can distinguish between external and internal attributes.

External attributes are how our product looks from the outside: graphical interface, money earned and spent, user behavior metrics.

Internal attributes are how our product is structured internally: company culture, work processes, colleagues' peculiarities.

In good old times, one could draw a strong equivalence between downstream and external attributes, as everyone prioritized maximizing external efficiency of the product/company.

I don't like color-based terms, but since they are popular these days…

The statement about the unconditional importance of external attributes is true for orange organizations, which are focused on maximizing external efficiency. It also holds true for the types of organizations that were before the orange ones.

However, for the rising new type of organizations — teal — some internal attributes can be as important as external ones, such as team culture, the number of trees planted, or the average lifespan of people in the neighborhood of a medical organization.

In the logic of this post, such internal attributes are also considered as downstream attributes, as they correspond to the "convergence points of the company's efforts". Therefore, throughout the remainder of this text, let's remember that downstream attributes can be both external and internal.

We want to manage the product measurably, preferably using quantitative metrics, which are essentially quantitative attributes of the product. It's just more convenient. When steering the product, we need to understand that we are currently in state A with certain attributes, and if we change something, we should arrive at state B with certain attributes within a certain time frame.

The longer the chain of cause-and-effect between the effort application point and the managed thing, the harder it is to steer, the more noticeable will be the divergence between actual changes and predicted ones. In other words, if we are interested in specific changes in attribute X, we should try to manage it through the node X itself or its immediate causal environment.

Individual major changes produce clearer and more traceable effects than multiple small ones. Multiple small changes lead to a complex network of dependencies and, consequently, a complex flow of non-obvious consequences that are hard to track and even harder to direct without mistakes. In this context, I like the advice of Sid Meier — a legendary game designer and creator of the Civilization series — about changing game balance parameters:

Double it or cut it in half. You are more wrong than you think.

Sketching out a hypothesis search strategy

Relying on the heuristics above, we can say that we are interested in hypotheses about measurable changes in individual downstream product attributes through measurable individual changes in their immediate causal environment. For example, the mentioned earlier case of reducing the churn rate through improving support response time.

Let's align this statement with the heuristics:

- We aim to use one lever to influence a small set of attributes.

- We aim to make hypotheses about changes in downstream product attributes.

- We aim to make hypotheses about measurable changes in measurable attributes, as downstream product attributes are easier to measure.

- We aim to avoid long cause-and-effect chains; for this, we manipulate the properties of the product from the causal neighborhood of the target attribute. More on long cause-and-effect chains and change propagation will be discussed below.

- We aim to minimize the number of change points.

In other words, we steer the product as a whole, rather than trying to control each part separately — this aligns with the conclusions from the previous post.

Analogy with steering a car

A car's control interface is designed for the driver to operate the vehicle as a single, unified whole.

- The driver can accelerate it, brake, estimate position using mirrors, and so on.

- The driver doesn't control each wheel individually, doesn't manage every spark plug, doesn't regulate tire pressure in real time, and so on.

There may be exceptions, such as sports cars, stunt vehicles, and other specialized things, but in the majority of cases, driving a car means operating it as a whole.

We can notice how the complexity of steering increases with the depth of control, in the example of gearboxes. Switching from automatic to manual transmission is quite challenging, even though the car itself remains conceptually the same.

Change propagation

Finding a lever that will change only a single product attribute is a near-impossible task. As we discussed in the previous post, a product is a highly interconnected chaotic system — a small change will inevitably ripple through the entire system.

That's why the point isn't in finding the perfect one-to-one change, like X → Y; neither is it in accounting for all possible consequences, all possible paths of change propagation.

The essence of a good hypothesis is to localize and predict, as precisely as possible, the changes that matter to us. Only then can we effectively use the prediction: change the product in a way we understand and achieve the result we need. Note that by significant changes, I mean not only positive ones but also negative ones.

For example, simplifying:

If we implement feature X, our LTV will increase by 10%, DAU will increase by 30%, we'll lose 1% of users (due to old PCs), and the rest of the metrics will fluctuate randomly by a small delta.

All other "side effects" that inevitably ripple further and deeper can be treated as consequences of the product's life cycle, and we can handle them in a routine manner. Sometimes this means some standard routine actions. Other times, we might overlook significant negative consequences and end up with a new major problem — everyone makes mistakes [ru] — this is a normal process, what matters is not the facts of errors, but their frequency.

Product metrics as levers and targets

Since we:

- Are interested in influencing downstream product attributes via their causal neighborhood.

- Treat the product as a unified whole rather than a collection of separate parts

- Want to manage the product through measurable properties.

We can say that we are interested in manipulating metrics of product behavior in the external environment — a quantitative measure of how it interacts with it. Typically, these are user interaction metrics, resource flows into and out of the product, and so on.

Moreover, these metrics can serve as both our target indicators and levers through which we attempt to influence them.

Let's at last discuss what's what.

Alternative terms

Amazon uses the terms input/output metrics in a similar sense to levers and targets in this text.

Also, I've encountered references to leading/lagging indicators as analogous terms, but in my opinion, they have a slightly different meaning.

Targets are defined by our product vision, its development strategy, and the logic of its immune system; they reflect our goals, values, and risks. They are something we absolutely want to achieve, increase, or prevent.

For example, if we are developing an MMORPG, one of our strategic targets will be user Life Time. It's critical for us, even apart from direct revenue, as the value of an MMORPG for a player is derived from its community. That means it's essential to keep active players around even if some of them don't generate much direct income. On the other hand, if we are developing a hyper-casual one-day game, then Life Time becomes much less important — we know that metric will be low — it's part of our strategy.

Risks can also be a source for target metrics. For instance, we might want to define a maximum acceptable time frame for fixing vulnerabilities. While this metric isn't directly linked to revenue, it can be part of our guarantees to users.

We cannot directly affect target metrics, but we can influence them indirectly through the causal network that links them to the levers at our disposal.

North Star Metrics

Targets are semantically close to North Star Metrics.

The term isn't fully established yet, but it roughly means "metrics that best predict or characterize a company's long-term success.

Let's not get bogged down in whether North Star Metrics are the same as our target metrics or not. It's enough that they are conceptually similar, and there are some interesting posts about them.

Levers are metrics that we can influence directly, they are under the team's direct control.

For instance, page load speed, support response time, the number of bugs in a release, user interface properties (quantitatively expressed, for example, in the time required to perform typical tasks).

Levers' metrics often can become a KPI.

The key difference between levers and targets is that target metrics are typically well-defined from the start, whereas levers require active exploration and identification.

We search for levers by tracing the chain of causality backward from the target metrics to the nodes we can control predictably and understandably.

The world is a complex place, and everyone makes mistakes, so it's not enough to simply identify some levers. It's also essential to retrospectively analyze how changes in those levers affect the targets — to check whether the hypothesis actually worked. If it didn't, there's a good chance we either wrongly assessed the lever's impact on the target metric or misdefined the metric itself.

Example of proper metric search from Amazon

Unfortunately, I haven't yet gotten around to reading Working Backwards — a book about Amazon's work culture, but I want to share a telling example from it. The example is taken from the post Goodhart's Law Isn't as Useful as You Might Think (I have notes based on it).

At some point, Amazon decided that the number of new product detail pages would make a good lever-metric. It was promoted to a KPI.

Soon, they discovered that teams had started creating a huge number of product pages for items that had no demand—this had no effect on revenue growth.

As a result, they had to kick off an evolutionary optimization of the metric, which went through several iterations:

- Number of product detail pages.

- Number of views of product detail pages.

- Percentage of views of pages for in-stock products.

- Percentage of views of pages for in-stock products available for delivery within 1–2 days.

The last version proved to be sufficiently correlated with revenue growth and became a lever that teams began using to influence the product.

Algorithm for hypothesis search

As a result of our reasoning, we can formulate the following algorithm for hypothesis search:

- Identify your target metrics (North Star Metrics).

- Map out a causal diagram connecting target metrics to "hypothetical" lever-metrics. Amazon provides a good explanation.

- Analyze each lever:

- How does it influence the target metrics?

- What significant side effects may occur in other product attributes?

- Select the levers that are practical to work with and formulate hypotheses like "If we increase metric X by N%, then target metric Y will grow by M% within T time".

- Choose the most promising hypotheses to implement.

- After implementing them, analyze how the product actually behaves, compare real-world metrics with expectations.

- If the hypothesis doesn't hold up:

- Either try to evolve the lever-metric — go back to step 2;

- Or abandon the hypothesis — roll back the changes or put functionality on hold.

- If the hypothesis works, continue following it.

Micromanagement as a consequence of long causal chains

Let's not forget to limit the length of chains between the lever and the target metric — we shouldn't engage in micromanagement.

For example, try not to manage revenue by hiring or firing people. Layoffs can be part of implementing a hypothesis, but they shouldn't be part of the hypothesis itself.

Incorrect hypothesis:

We will increase revenue by 10% in 3 months if we hire 5 new developers.

Correct hypothesis chain:

- "We will increase revenue by 10% in 3 months if we implement feature X" => we launch "Project X" — create a subsystem "Project X" about which we can also hypothesize.

- "To implement 'Project X', we need a team of 5 people" => we launch "an activity to find 5 people" — create another subsystem with its own hypotheses.

- "Hiring 5 people in the current situation is more profitable than taking 5 people from other tasks" => we launch "activity to hire 5 people" — an even more localized activity that can also have its own feedback loop.

- …

Hypotheses with the short causal chain are also good because each of them creates a fork in planning — a point for searching opportunities, a point for possible maneuvering (if something goes wrong).

If we follow an incorrect hypothesis, like the one about hiring 5 developers, and it doesn't work out, we roll back to the very beginning. If we follow a chain of hypotheses, we only take one step back.

Side notes

There are a few additional points I'd like to highlight.

Strictly following formal processes may be a good thing, but overdoing it can backfire.

Don't lose your head and prioritize formality over common sense. The smaller your company or team, the more resources will be eaten up by meticulous hypothesis crafting, metric tracking, dashboard maintenance, and so on — leaving less time for the actual work. It's always wise to seek balance and cut corners where it makes sense.

It's much easier to objectively measure a product's interaction with its environment than to measure its internal state. Don't try to quantify culture or people — especially using blunt metrics. It will always backfire. In the previous post, we discussed the importance of self-organization; superficial metrics and KPIs are its greatest enemies. If you want your teammates to stop communicating, stop learning, and stop helping each other, just give them conflicting quantitative KPIs.

This post is a part of series

- Next post: What to read, when, and why

- Previous post: Points of view on a product

Read next

- Two years of writing RFCs — statistics

- World Builders 2023: Preparing a business plan for a game on Steam

- Dungeon generation — from simple to complex

- Generation of non-linear quests

- Summa Technologiae book review

- Pricing model at the start of Feeds Fun monetization

- On the roles of function and selection in evolving systems

- Prompt engineering: building prompts from business cases

- Thinking through writing

- World Builders 2023: Preferences of strategy players