Generation of non-linear quests ru en

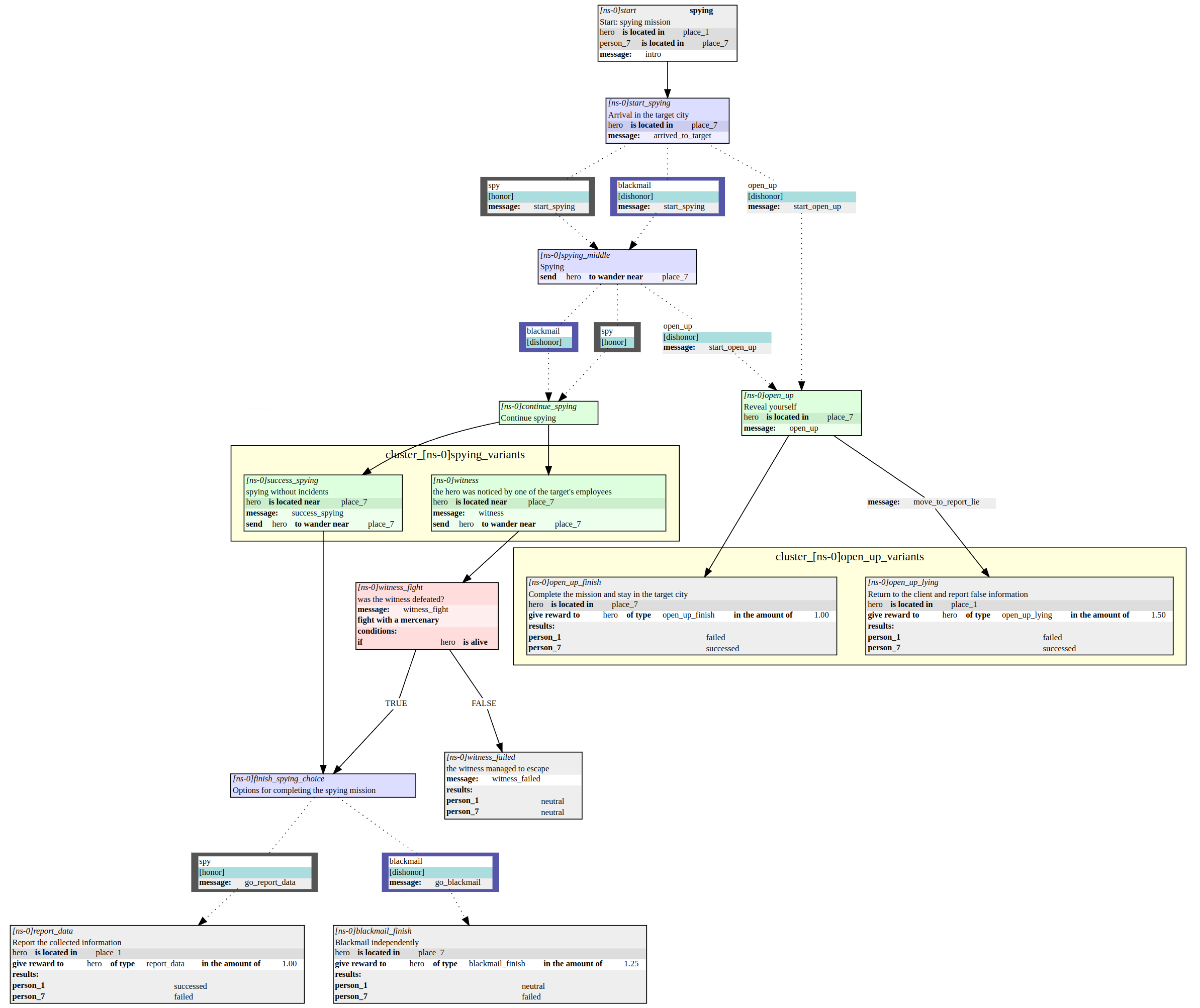

Non-linear quest with nested sub-quest

This is a translation of the old post

This is a translation of my post from 2013 about quest generation for the now-stopped game The Tale. I think it is still relevant, interesting, and could inspire other developers.

Please remember that the original post was written in 2013. I updated part of the post, but some statements and ideas may be outdated, and the flow of thoughts is not as clear as it would be if I had written this post now.

Despite the fact that the conception of automatic quest generation in RPGs is quite old, there are almost no publicly available working versions of such generators (rather none at all) if we do not count primitive ones. There are also not many posts on this topic, although some can be googled. So, I hope this text and the quests generator will be helpful.

You can find examples of generated quests in the repository.

Why the generator was needed

ZPG — Zero Player Game — is a game without active player interaction. The closest popular analogs are Godville and Progress Quest.

"The Tale" was intended to be that kind of game — a text multiplayer role-playing game in a persistent fantasy world.

The player's character (hero) in the game acted completely independently, and their main activity was, of course, completing quests from NPCs.

A key point of the game was that the quests had to be non-linear, and the player should have a choice of which NPC to help and which to harm. Players' choices directly influenced the "fate of the world". For example, an NPC could leave the game permanently if many players harmed them.

Besides, the hero had a "character" that could influence his actions when completing a quest. For example, he could be set to help a specific NPC or prefer honorable actions/decisions.

Therefore, I required a way to automatically generate complex believable quests that would not contradict the game world and require the player to think before making a choice.

In the following text, I will use the term "story" instead of "quests" as a more convenient for explanation: each quest is a story limited by a couple of conditions, so it is more reasonable to talk about a story generator.

Requirements

The base requirements for the generator were as follows:

- Non-Linearity: any number of branches and endings should be possible;

- Nesting: one story can have any number of nested or sequential sub-stories;

- Integrity: the story should always have a correct ending, no matter which path the hero takes;

- Feasibility: the hero should be able to complete any story in a finite time;

- Consistency: the story should not contradict the state of the world or itself;

- Scalability: the story can have any number of "actors" (players or NPCs);

- Variability: the stories should differ from each other, even if they are about the same thing in general.

Besides the requirements for the stories themselves, there were several requirements for the generator:

- If the generator creates a story, it should be correct (i.e., it should comply with all requirements);

- The stories should be visualized in a convenient way for the developer;

What is a story

Knowing the requirements, I had to define what a quest or a story is. In the end, I came to the following definition.

Definition of a story

The story is a directed acyclic connected graph. The nodes describe the state (requirements for the state) of the participating entities and the environment at a specific stage of the story, and the edges define possible transitions between these stages.

From the definition, it smoothly follows the idea of implementing the story as a state machine, which is transferred from the quests generator to the game logic engine.

So the generator had to create a story graph based on the information about the current state of the world with respect to the requirements listed above.

The game logic will interpret this graph. It will initiate the necessary changes in the actions of the hero or in the environment based on the information about the current state of the story and the expected future state, leading to the fulfillment of all requirements necessary for the story to move to the next stage.

Here is an example of such an interpretator

The structure of the story

So, the story is a graph consisting of nodes and edges. Each node has a list of requirements (or checks, if you like) that must be met for the story to move to the corresponding node. A requirement can look like the hero is in a specific place or the hero has a certain amount of money.

Besides the requirements for the world's state, each node has a list of actions that must be performed when the story reaches this node. Such actions could be implemented as separate nodes with requirements, but it would significantly increase the graph complexity. You may look at them as a semantic sugar :-) Action, in our case, could be send a message to the player, start a battle with a monster or give a reward to the hero.

Edges have the same lists of actions assigned to the beginning and end of the edge.

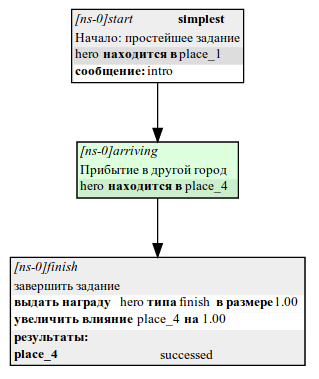

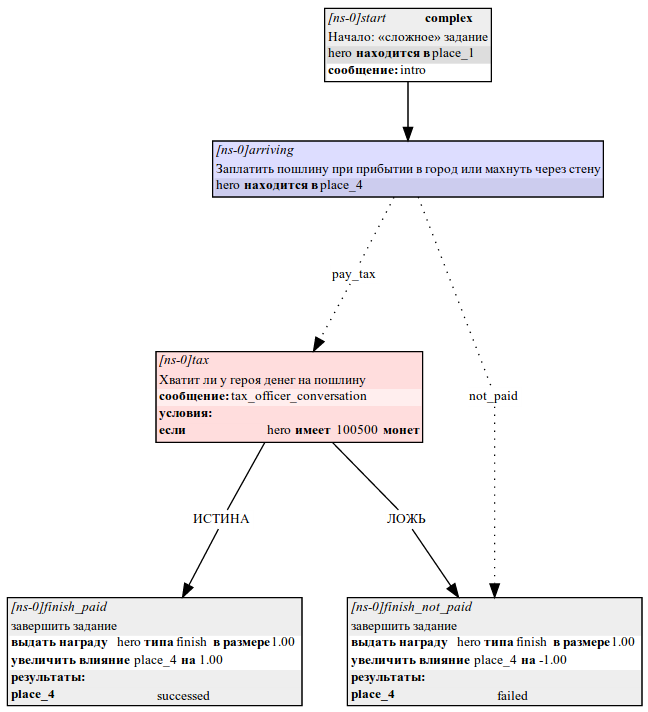

An example of a simple story.

Legend for the graphs on the pictures

- gray nodes — the beginning and end of the story;

- purple nodes — choice points;

- green nodes — ordinary story points;

- red nodes — conditional transitions;

- cyan contours — sub-stories;

- dark background in the nodes indicates requirements that must be met for the story to move to this node;

- light background indicates actions that must be performed immediately after the transition to the story point;

Transitions between nodes can be represented as a loop:

- Choose an edge of the graph along which the story will move.

- Perform actions assigned to the beginning of the edge.

- Wait until all requirements of the next node are met.

- Perform actions assigned to the end of the edge.

- Move the story state to the next node.

- Perform actions assigned to the node.

- Return to the beginning of the loop.

The nodes of the story can be separated into types that define their role:

Start— the only entry point to the story or sub-story. The requirements of this node must guarantee that everything will go correctly, whatever path the story takes;End— the marker of the end of the story or sub-story;Choice point— a node where the hero (or player) must make a choice about the further path of the story;Conditional transition— a node where the further path is determined by some dynamic parameter, for example, the amount of money the hero has;story node— a node that has no additional properties, it just defines the next event in the linear sequence of the story.

An example of a more complex story.

Story generation

The story can consist of several atomic tasks. For example, a sick NPC can send the hero for medicine to a witch, who will require a service (performing another nested task) in exchange for a remedy.

That's why the story is built from a set of atomic templates. A template is a graph of the story with all possible branches (even those that can break the story).

The important part here is the connection of templates (remember that we need a connected graph at the end):

- At least one node of the parent story must have an edge to the start node of the child story;

- At least one end node of the child story must have an edge to the node of the parent story.

After some experimenting and thinking, I came to the conclusion that all stories can be characterized by a set of key objects/variables (places, characters, items). Therefore, each template has a set of constructors that take data in a fixed format. Here are some examples of constructors:

start a quest from a specific place— if we want the story to start in a specific place, and everything else can be random;start a quest affecting two NPCs— when it is necessary for one NPC (initiator) to initiate a task related to the second NPC (recipient);

When generating a child story, the parent story filters all templates based on the presence of the required constructor, one of which is then randomly selected.

We connect the parent with the child by linking the child's start and end nodes with the parent's nodes.

We create an edge from a node in the parent story to the start node of the child story.

There may be several end nodes in the child story, and they can have different semantic meanings for the plot. For example, in the story about a witch, the hero can not only complete her task but also fail, which may push the witch to refuse to help the hero. Therefore, edges from different end nodes must be strictly directed to the distinct corresponding nodes of the parent story.

To achieve this, we define a set of semantic results for each entity participating in the story in each end node.

There are three possible results:

positive— the story has a positive influence on the entity;neutral— the story does not influence the entity;negative— the story has a negative influence on the entity.

With the help of such info we can find the correct nodes in the parent story for end nodes of the child story.

Postprocessing and validation

After merging multiple templates into one graph, we obtain a visually correct story graph, but without any consistency guarantees. The graph contains all possible paths of the story, even those that contradict the state of the world or the internal logic of the story.

For example, in one of the story branches the hero can harm his friend. Or two NPCs marked as enemies can act together.

Therefore, the story must be additionally processed. Such processing includes the following steps:

- Some nodes may be grouped into clusters of alternative story branches. One node is selected from each group, the rest are removed.

- All end nodes with forbidden semantic results for the entities are removed. For example, if the hero is a friend of the NPC, then the end node of the path where the hero harms this NPC will be removed.

- The resulting graph is cleaned of hanging nodes. "Hanging" nodes are the following types of nodes:

- a node that is not an end node of the root story and has no outgoing edges;

- a node that is not a start node of the root story and has no incoming edges.

The final graph, at least, will be consistent. However, it can become infeasible or disconnected, meaning that the story will become incomplete. Therefore, the next step is to check all the requirements of the resulting story.

If the requirements are met, the story is ready for use. The game engine will be able to interpret it correctly.

If not, we drop the story and start generating it from scratch.

The approach with complete rollback can lead to a very long generation time if the game world is tiny and has a lot of connections. In practice, there are usually many objects in the world and few connections between them, so this does not pose a problem.

In the case of frequent errors, the game can reduce the number of world properties passed to the generator, for example, stop taking into account the friendship relationship. The generator itself does not try to make additional assumptions about the state of the world.

Read next

- Dungeon generation — from simple to complex

- World Builders 2023: Simulating public opinion in a game

- Concept document for a space exploration MMO

- World Builders 2023: Preferences of strategy players

- World Builders 2023: Preparing a business plan for a game on Steam

- «Slay The Princess» — combinatorial narrative

- World Builders 2023: Cleaning up the results of the strategy players survey

- World Builders 2023: Procedural news headlines without complex text generation

- Using DALL-E-3 for Game Development

- Two years of writing RFCs — statistics