«Slay The Princess» — combinatorial narrative en ru

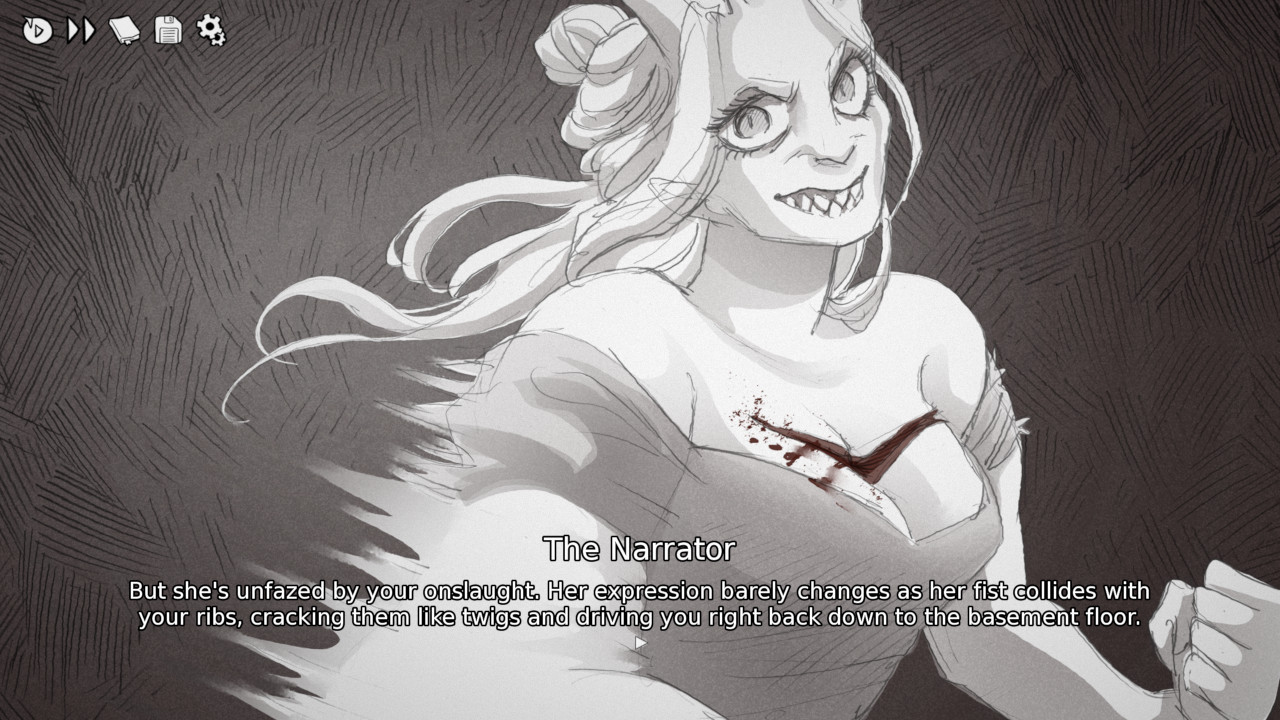

My favorite version of the Princess.

It's hard to impress me as a player and even harder as a game developer. The last time it happened with Owlcat Games in Pathfinder: Kingmaker, when they added a timer to the game's plot.

But Black Tabby Games managed to do it. And they did it not with some technological complexity but with a visual novel on a standard engine (RenPy), which is cool in itself.

I'll share a couple of thoughts about the game and its narrative structure, while I'm still under the impression. I need to think about how to adapt this approach to my projects.

ATTENTION: SPOILERS!

If you haven't played Slay The Princess yet, I strongly recommend you to catch up — the game takes 3-4 hours. You'll not regret it.

Sequence of interesting choices

I started the draft of this post thinking that «Slay The Princess» is not a game but an interactive experience. In the process, I realized that I was wrong. There is an interesting nuance with «The Princess».

For example, let's take Sid Meier's definition that a game is a sequence of interesting choices.

Usually, I interpreted it as a "sequence of interesting game-mechanic choices" — choices that affect the state of the game in an interesting for the player way. I assume that most developers implicitly interpret it this way.

There are almost no such choices in «Slay The Princess». And you can't "lose". The developers even warn you about it in a tricky way at the start of the game.

The choices made by the player in the first 99% of the game have little effect on the course of it and do not affect the ending in any way. There are a few exceptions, but they only confirm the rule. All significant choices for the ending occur in the last 5-10 minutes.

If you've read this far and haven't played the game yet, congratulations, killing Princess will be much less enjoyable for you.

The player's choice in «Slay The Princess» affects not the state of the game but the state of the player — what they experience while going to the finale. An essential part of this influence is the lack of knowledge of what the choice changes.

So, if we cut the "game-mechanic" part, then «Slay The Princess» is definitely a game, just not a traditional one? non-standard? or just a game as it should be?

It's curious that "mechanically insignificant" choices are not uncommon in games but rather the standard. They are used in role-playing games, visual novels, CYOA, and other genres — always when you need to influence the player's emotions on the cheap. Usually, it turns out poorly. I've played enough in different genres, but I can count on my fingers when it worked on me.

But in «Slay The Princess», this is the basic mechanic, and it somehow works great.

Game loops

Mechanically, the game is "simple". There are three cycles:

- You stand on the road to the forest cabin, enter it, (do not) take the sword, go down to the basement, and do something with Princess. Usually, as a result, one of you dies, but not always.

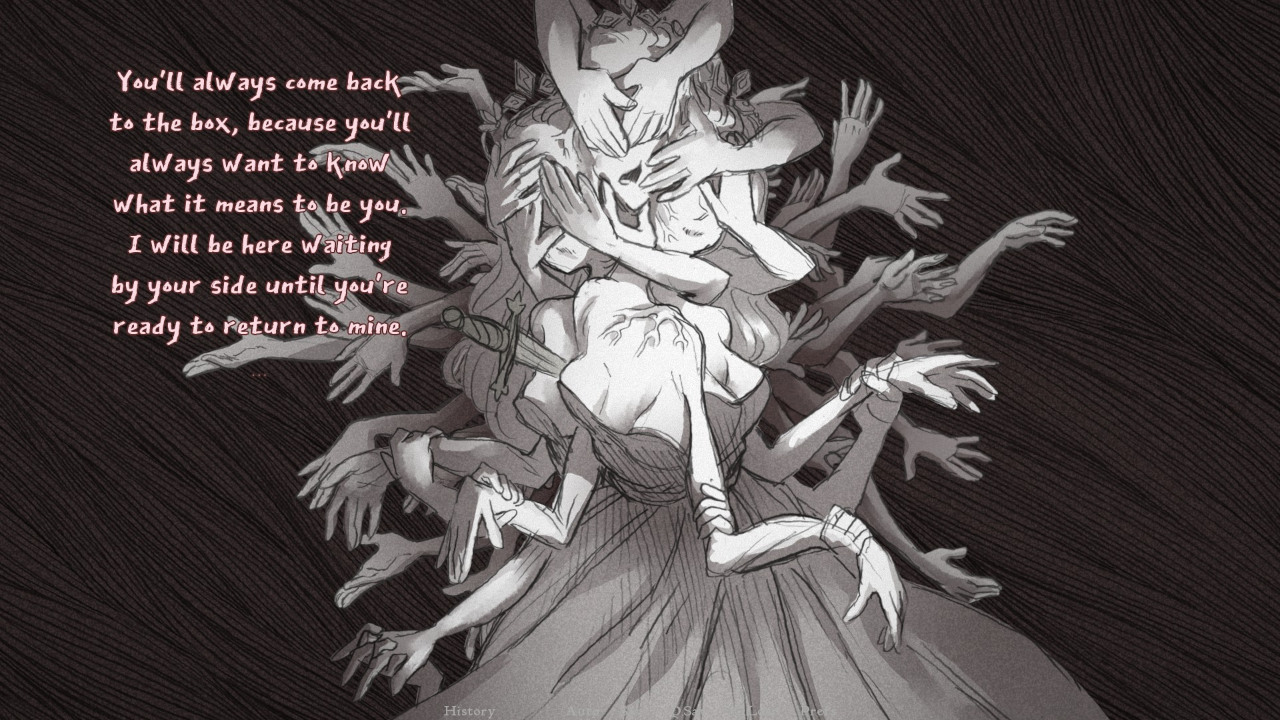

- You repeat the first cycle about three times, each time Princess and the cabin change due to your choice in the previous cabin. I want to say Princess is transforming, but in reality, she's being brutally twisted. More on that will be later. At the end of the cycle, the god-like entity Mound takes Princess, thanks you, erases the character's memory and returns the player to the beginning of the cycle.

- You collect 5 princesses for Mound and get the finale — this is the whole game session.

The cabin — cycle 1

The first cabin.

The first cycle:

- You are placed in a context: starting (if you are at the beginning of the second cycle) or the one you created by your choice in the previous cabin.

- You should solve a moral dilemma in conditions of uncertainty: kill the Princess or not.

- Mechanically, it is organized as a classic visual novel: you go through several locations, choose dialogue options, etc.

During the first playthrough, the player probably won't be sure if they should kill Princess, if it is fair, and how this killing will affect them and the world. The player is put in a situation of complete uncertainty where everyone lies hides the truth, and the player should restore the general picture from reservations, insinuations, and own imagination. This mini-detective, by the way, deserves special praise — I haven't been so confused in a long time :-D

It turns out that on each iteration of the basic game cycle, the player is not given trivial tasks like "kill 100500 boars" but is forced to solve a moral dilemma about the central element of the game, its cornerstone. Princess, in the end, is in the title of the game. Everything is about Princess, even you — the player — is about Princess.

It is important that you cannot repeat a choice in the same situation. If you've intentionally missed with a dagger at Princess once, you will have to kill her the second time in the same situation.

Firstly, at the beginning, it leads to something like moral dissonance when the player is forced to go against what they think is right at the moment.

Secondly, it forces the player to plan actions more carefully at the level of the game session.

Also, killing or saving the Princess affects nothing except your inner state. But you will learn about it only post factum. Somewhere in the middle of the game, Mound will hint you that your choices of princesses do not affect anything in the spirit of "it's not about that," but in the conditions of narrative paranoia, this hint personally for me changed little, and the logic of what is happening says that choices should affect something.

Princesses as psychological archetypes — cycle 2

Princesses, official art.

I'm not a psychologist, so I can make mistakes in terms.

As I said, the essence of the second cycle is that you change Princess with your interaction with her.

Finishing the cabin leaves a mark on the poor thing: sometimes "bad," sometimes "good." This mark makes her an embodiment of one of the psychological archetypes: Rage, Anger, Love, Betrayal, Power, Thrill, and so on — there are many of them. Archetypes are written with a capital letter because these are not minor changes, they fully rewrite reality: Princess changes visually, her manner of communication changes, her voice changes, the cabin changes.

I want to give the developers special respect for the systematic & systemic rewriting of Princess — it's really cool.

In a new cabin, a player has to decide what to do with the consequence of their moral choice in the previous one:

- What should I do with the Betrayal I committed?

- Should I destroy the Hope I gifted?

- Should I extinguish the Passion I ignited?

A journey through the cabins invariably ends with a kind of catharsis, after which Mound takes your unique, hard-earned Princess, and you return to the first cabin.

The second cycle is essentially a classic branching plot tree (more precisely, DAG).

But, unlike in most other visual novels:

- It is not deep. If we count in cabins, everything is usually solved in 2-3 cabins, but there are more branches: usually, within one cabin, there are several decision points. On Reddit, there is an almost complete scheme.

- With sharp transformations in decision nodes. For example, even the first choice in the first cabin "take or not take the sword" leads us to different princesses.

- With blocked paths due to your previous choices.

Combinatorial narrative — cycle 3

Mound.

If we count by princesses, there will be 20 variants of the second cycle.

In reality, there are more because the Princesses can transform into each other. However, it is not easy to count the full number of paths through the second cycle, and princesses will not repeat. So we can stop at a minimum of 20 — it will be more than enough for our purposes.

We remember that the player needs to collect 5 princesses, aka pass the second cycle 5 times.

Given the general misunderstanding of what is happening in the plot, we can assume that players will "open" different princesses and do it in a different order. Of course, there will be some patterns in the spirit of "many will try the most violent approach," but in general, this process looks quite random.

Let's remember combinatorics and find the number of arrangements without repetition of 5 out of 20 elements.

n!/(n-k)! = 20! / (20-5)! = 20! / 15! = 16*17*18*19*20 = 1860480

In total, we have a minimum of 1860480 variants of a deeply personal experience for players — based on "strong" choices of "life vs death," "trust vs lie."

In other words, the game gives more than 1.8 million ways to lead the player through psychological states (Rage, Anger, Love, etc.)

Again, such combinatorics are not a unique feature of «Slay The Princess. Most RPGs do the same: go do quests at point A, then at point B, or, if you want, vice versa, first at B, then at A. Add a couple of such points, let someone be saved or killed there, and you will also receive some "uniqueness" of the experience with "strong choices," but it will not work as effectively.

Known unknown

Mechanically, the game looks simple, I think I understand how it works, but this only raises more questions in front of me:

- Why, with such simplicity, do so few games achieve such effectiveness in influencing players?

- Is the success of the game a consequence of the successful/correct combination of standard mechanics, or is there something else non-obvious?

- What mechanics in «Slay The Princess» are mandatory, and which can be removed or changed?

- What is primary for success: leading a player through psychological states, narrative combinatorics, or both factors are equally important?

- Can such an effect be achieved with more grounded player choices?

- Can such an effect be achieved with less elaborated images and sound?

- Can such an effect be achieved without limiting the information available to the player?

- How important is the player's fast journey through psychological states? Can this journey be stretched for 20-30 hours?

I don't know the answers yet. The key might lie in quickly leading the player through vivid extreme psychological states, but I'm unsure how important it is.

Some interesting game features

After visiting the cabin, not only Princess and reality change but also the player's character. Separate voices appear in the hero's head, corresponding to what happened. For example: Lover, Paranoid, Helpless, etc.

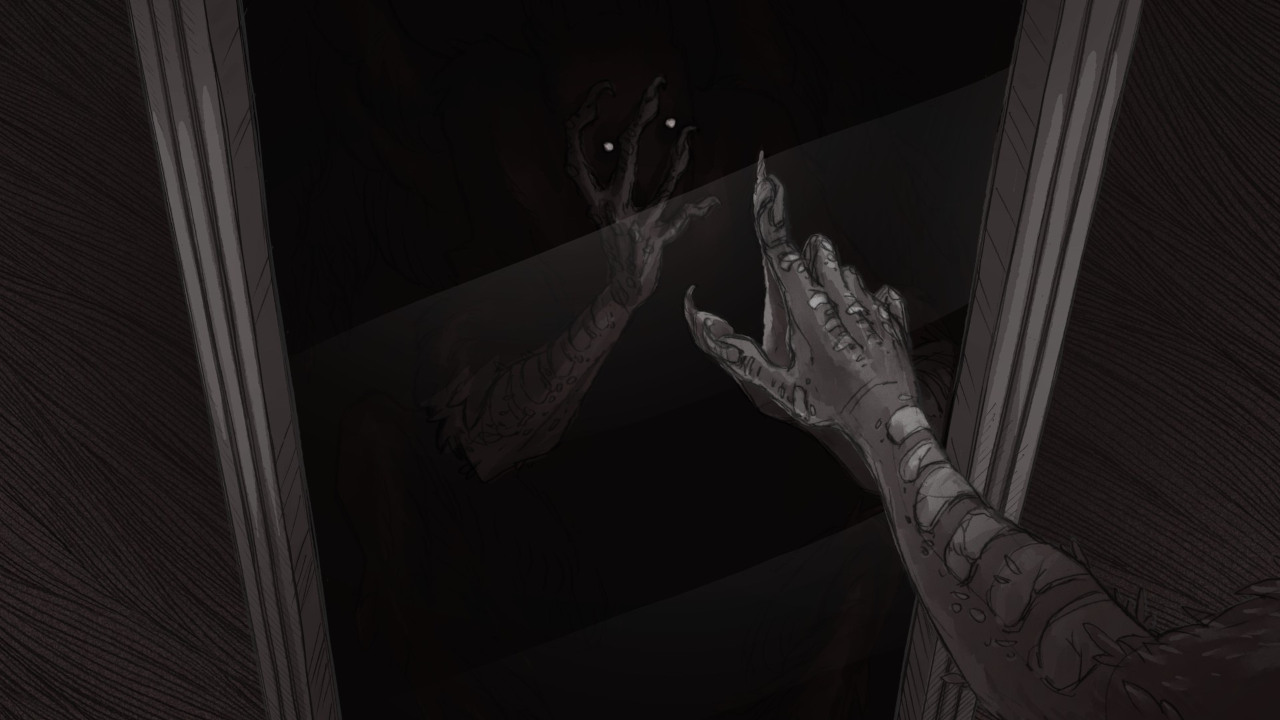

The player is "the hero" (like the Princess is "the princess"), but not a human — a rather creepy creature. Princess is also not always a human, but always starts as a human and is built around humanity. The inhumanity of the hero does not bother Princess, but it may bother the player when they notices it. In a sense, inhumanity breaks the stereotype of the "hero who saves the princess."

The hero.

In the finale, the player can "argue" with his princesses.

At the start of the game, the developers say it's about love. They don't lie.

Read next

- Dungeon generation — from simple to complex

- Generation of non-linear quests

- How to design a dungeon

- World Builders 2023: Preferences of strategy players

- World Builders 2023: Preparing a business plan for a game on Steam

- World Builders 2023: Simulating public opinion in a game

- Concept document for a space exploration MMO

- Two years of writing RFCs — statistics

- Thinking through writing

- Pricing model at the start of Feeds Fun monetization