World Builders 2023: Preparing a business plan for a game on Steam en ru

Earning millions is easier than ever. I'll tell you how :-D

Notes on my participation in World Builders:

- Cleaning up the results of the strategy players survey

- Preferences of strategy players

- Procedural news headlines without complex text generation

- Simulating public opinion in a game

- Preparing a business plan for a game on Steam

When I posted my final presentation [ru] (slides) for World Builders 2023 (my posts, site), I promised to tell how I made a roadmap and a financial model for the game. So, here they are.

At the end of this post, we will have:

- A brief strategy of our company: what we do, how, and why.

- A table with our beacons — successful games roughly similar to what we want to make. Similar in gameplay, team size, budget, etc.

- A composition of the team we need to assemble.

- A roadmap — a development plan for our game.

- An outline of our marketing strategy.

- A financial model — how much we will spend, how much we will earn.

- A large number of my caveats throughout the post.

- Jokes and

I hopewitty remarks.

All the final documents can be found here.

Disclaimer

Attention!

Following this post and my logic as a whole is strictly on your conscience and responsibility. Think with your head before copy-pasting.

In case you lose millions of dollars following this post, and gloomy guys come to you with questions, please do not redirect them to me. Take responsibility with your head held high, even if your legs are already set in concrete. Just kidding, do not deal with non-specialized investors, and your health will be fine.

Here is why you should critically look at this tutorial:

- I'm not a professional businessman. I had a business and spent more on it than I earned.

- This is the best of two business plans I've ever made. The fact that it is the best does not cancel the fact that it is the second.

- I have not yet received money for it, and even the person looking for investors is not me. So, I do not know how investors will react to these calculations.

- This business plan was prepared as part of my studies, not as part of "I put my soul into opening my company and investing all my time and resources into it."

- It is possible to make it 100500 times better, but I did not. Pa-ra-pa-pam. Because there was no time, and sometimes I was lazy.

Iterative development

During the reading, it may seem that all the work can be done sequentially from beginning to end. This is not the case. I post-factum organized everything into a narrative form to save you from jumping chaotically between documents.

Move in a spiral

While developing your business plan, you will find mistakes in your logic, calculations, data, and everything else. You will forget things and then remember them. So you will have to jump between different documents, iteratively adapting them to each other's constraints. This is normal and should be so in any healthy development of a complex thing.

But if you don't do it this way and try to force your way through, you will definitely make a mess. Not that I didn't make a mess.

So.

Define company strategy

Imagine, for some reason, you've decided to make a game for the indie developers' graveyard Steam. And it's a single-player sandbox strategy game (see presentation if you are interested). Maybe with multiplayer, but you're not sure yet.

Listing the possible reasons for these decisions is beyond the scope of this essay.

For example, if you focus on earning money (why then go into gamedev?), you should find reports on different platforms, see which genres make money on which platform, evaluate the average team size, investments, and development time, and make a weighted decision to create a free-to-play mobile MMORPG for low-grade mobiles in the African market or something like that. Just in case, I'm serious about Africa.

Why I decided to do what I do

I chose the entertainment sphere because the school is about making something in this area.

Games (not comics, movies, books, etc.) were chosen because I have good expertise in gamedev, the school's primary expertise is there, too, and most residents decided to make games. I didn't want to break away from the team and spend more time than I was willing to spend.

Mobile games are a simulacrum — a form triumphing over conten [ru] with a marketing budget larger than the development budget. Not interesting. It's funny, but in our final financial plan, the marketing budget will also be larger, but, of course, it's different :-)

VR, consoles, and other things are more complex (for me) regarding technology and game design.

PC platform remains dominated by Steam.

Strategy and RPG are the genres in which I played the most I have the most expertise, and which I like. Plus, they allow developers to reveal the world better. Revealing the world is one of the school's requirements for the product.

MMORPGs are also interesting to me, but my view on them radically differs from any person similar to an investor, so not this time.

In my opinion, it is much easier to make a good strategy (even with RPG elements) than a good RPG. Because creating an RPG with a linear plot is not fun, and developing a non-linear plot makes me tremble with combinatorics and the pain it will cause.

Choosing monetization the main financial flow

There are several approaches to monetizing games on Steam:

- Through major releases.

- Through selling DLC — Downloadable Content.

Through microtransactions

In my world model, the company should aim for one thing and use the rest as an additional source of income. If you try to catch two hares, you usually catch none.

I will not consider microtransactions, as in the field of single-player PC games, only AAA studios now how can allow themselves to do so, and only through giant marketing budgets and reputation loss. Indie developers will be buried alive by the Steam community for such a thing, and rightly so. Not to mention, I have no desire to mess up my karma.

Therefore, we have several options for the basic strategy:

- Make a major release of "My Mega Game". Move on to something else.

- Make a major release of "My Mega Game". Move on to something similar: make a sci-fi strategy after a fantasy one.

- Make a major release of "My Mega Game". Make a major release of "My Mega Game 2". Make a major release of "My Mega Game 3". And so on.

- Make a major release of "My Mega Game". Release a couple of DLCs. In parallel, work on something based on plan 2 or 3.

- Make a major release of "My Mega Game". Endlessly release DLCs.

There was a concept of add-ons in the old days, but for simplicity, we will consider them the same as DLCs. At least, I don't see any significant differences for the purposes of this post.

Option 1, in my opinion, is almost never practiced now, in the case of a successful product. It wastes a lot of resources: the team's expertise, the code, the pool of freelance specialists, and the community are all lost. It's not very profitable. But some especially dedicated indie developers might do it just for fun.

Options 2 and 3 are close. They can even be alternated. They allow you to reuse more artifacts of work than option 1. The downside is a very uneven flow of money, and it's not guaranteed, which means holes in the budget.

Is it easy to repeat success?

If you made a good game once (in ±two years), it doesn't mean that the second time it will be better or the same or that your players will forgive you for the same mistakes you made the first time.

The series of big releases is a risky venture. Therefore, in case of the success of the first release, many developers try to release at least a few DLCs to support the development of the next game. Which brings us to the fourth option.

Option 4 — releasing DLC in parallel with the development of the next game is a good way to reduce risks and make the life of the studio more predictable.

The problem with this approach is that not all teams can make a game that will be relatively easy to modify interestingly for players. Plus, not all genres are well suited for DLC.

For example, RPGs make it challenging to add each subsequent DLC because the game follows a single narrative. This makes it difficult to change mechanics (due to a campaign balance) and to extend the story (since good games are released with a complete and consistent storyline).

DLC as separate companies in RPG

Strangely, I can't remember any RPG where separate campaigns were released as DLCs. Aka with stories that are unrelated to the main plot and require creating a new character.

It may significantly simplify the lives of developers. And it would be much more convinient for me as a player to create a new group six months to a year after the first playthrough rather than remembering the plot and the mechanics of 100 abilities in the old save.

But if we don't have such problems, we can look at option 5 — replacing the main money flow from the releases of new games to the releases of DLCs. I call it the Paradox way because they are the best at it, as I see it.

The first release still brings a significant share of income, but the development focus is initially on the production of DLCs, which eventually outweighs the profit from the first release.

Option 6 — endless development of the base game

There are a few games, for example, No Man's Sky, Stardew Valley, developers of which continue to polish the base game (without DLCs) and continue selling it.

It's incredibly cool, and the developers deserve all sorts of praise. But I believe such a decision is made when you have already hit the target. Not even hit the target but, like Robin Hood, split the arrow in the bullseye. This decision can be made after the release of the first version when you already have money and a growing community, and you see THE POTENTIAL.

I can not recommend building a business plan based on such an optimistic scenario.

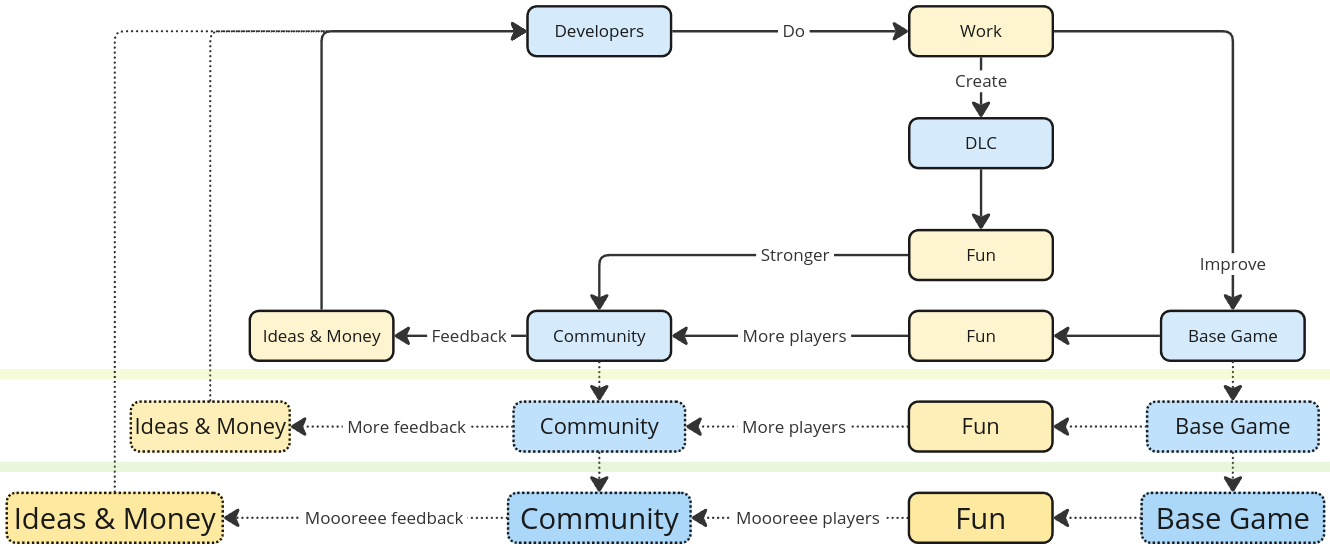

Massprodusing DLCs

The efficient, well-organized production of DLCs is great for two reasons.

Firstly, it forms a resilient developing ecosystem uniting the company and the player community:

- With each released DLC, you improve the base game, tune it to a specific niche, and eventually become a monopolist in it.

- Improved base game continues to be bought by players for whom it was not so good before. Therefore, your community continues to grow long after the release.

- A strong community provides quick and high-quality feedback for your decisions, leading to the release of better DLCs. Good DLCs improve the game. The improved game attracts people to the community. The community provides even better feedback.

This is how I see it. Money, in fact, is also a form of feedback.

Secondly, you get a predictable cash flow:

- The period between money inflows decreases from 1-2 years to 3-6 months.

- The risks associated with errors are reduced. In case of a failed major release, studios often close. In case of a failed DLC, you release the next one. The studio lives as long as it can learn from its mistakes.

- You sell DLCs not to random people but to your players. This makes marketing cheaper and income more predictable. You know how many people play your game and what percentage bought the previous DLC, so you can estimate how much money the next one will bring.

However, there are downsides:

- It works not with all genres. I think only with strategies and maybe sandboxes.

- The first release must still be quite noticeable and high-quality to form the core of your community. Paradox can afford to release mediocre products (judging by the reviews) and then polish them. But this is more of an exception — they are forgiven.

- You should know how to make games and how to listen to players. Not everyone can do this, and not everyone wants to.

Since we are making both a strategy and a sandbox, and in a free genre (public opinion simulation), we can risk and aim for the fifth option. In case of problems with organizing a pipeline for DLC production or with quality, we can always switch to the fourth option.

Early Access

An experienced developer may have noticed that I have bypassed Early Access.

I did this for several reasons:

- Now it is de facto standard. There is no point in skipping Early Access. The earlier you do Early Access, the earlier you get feedback from the universe [ru], the earlier you fix mistakes, the better the game will be.

- From my point of view, what exactly to release in Early Access is defined not by monetization but by marketing, team capabilities, and investors' wishes.

There are two poles:

- Full release in Early Access. We release what we would release in a regular release, only now we are forgiven more bugs, and the team is calmly working on the day-one, week-one, month-one,

year-onepatches. When everything is sold, we make a release to highlight the game for players who, for some reason, missed Early Access. - "Quiet" release in Early Access. We release a minimal, consistent integral game but significantly cut its features. We work hard to polish and improve the game based on players' feedback. When the game is ready, we make a "loud" release.

In my opinion, the second approach is unconditionally more effective. It provides feedback much earlier, which inevitably increases the quality of development at its final stage — if the team is ready to hear feedback, of course.

But not everyone can afford this:

- There is a risk of wrongly defining what a "minimal integral game" is. If you release the wrong thing, you will quickly fall into the limbo. You may not receive money for the final development stage if you have financing by rounds.

- Your game may be initially designed minimally, for example, due to budget constraints. That is, you will have nothing to cut from it.

- Marketers or investors will shift the development schedule so that you simply cannot release with the necessary set of features: "full release by Christmas or death."

Final strategy

- We are making a sandbox strategy for Steam.

- We are focusing on the long-term release of a large number of DLCs.

- We aim for a "quiet" release in Early Access, cultivating a community, actively exploiting feedback, and making a "loud" release when the game is ready.

- If the release of DLCs isn’t financially effective enough, we shift to developing a new game (a sequel or a game in the nearby genre) while still supporting the first game with a few additional DLCs.

Based on this strategy and our understanding of gamedev, we can describe the major stages of our work.

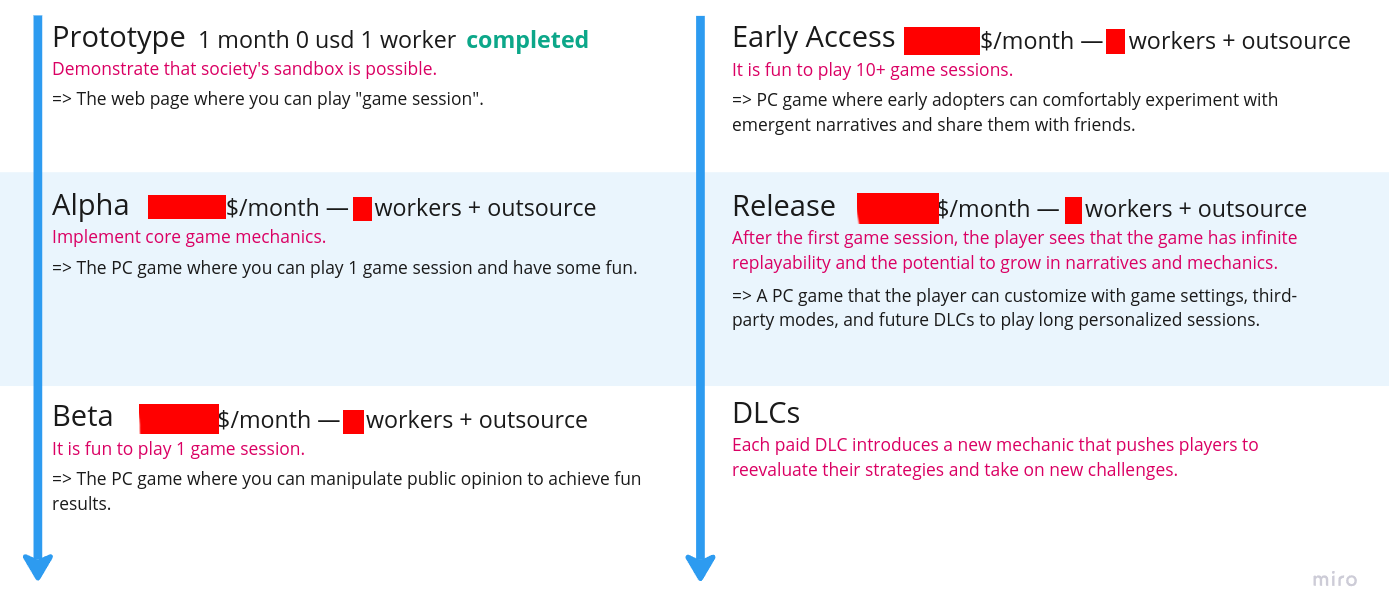

A slide from the presentation. The numbers are hidden — we don't have them at this step. The main goal of each stage is highlighted in red. Below its brief description.

Roadmap

Now, we need to estimate the amount of work. To do this, we unfold the stages of development into large tasks and estimate the time required to complete them.

The final roadmap can be found here.

The roadmap consists of three tables. For convenience, I highlighted their headers in color:

- The Red table contains all the major tasks we need to do.

- The Blue table shows the volume of tasks by tracks and stages.

- The Green table calculates the final time estimate for each stage.

We fill in the red table.

The Blue and Green tables are calculated semi-automatically: we set part of the values, and we take part from other tables. The Blue is calculated based on the Red, and the Green is calculated based on the Blue.

Red table

Here is an example from the beginning of the table, if you are too lazy to open the original:

| Stage | Epic | Feature | Track | Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Game skeleton | — | development | 10 |

| Alpha | Game design simplification | We should simplify game design, comparing to prototype | game design | 2 |

| Alpha | Game design simplification | We should simplify game design, comparing to prototype | development | 5 |

| Alpha | Base user interface | User journey specification | game design | 3 |

| Alpha | Base user interface | UI Schemas | game design | 4 |

| Alpha | Base user interface | Game Sketches | art | |

| Alpha | Base user interface | Sketches with GUI | art | |

| Alpha | Base user interface | Implement base UI | development | 10 |

Columns:

Stage— the development stage at which we need to complete the task.Epic— a large piece of work that we do as a team.Task— a piece of an epic that should be done by specific specialists, such as developers or game designers.Track— what specialists do this task: developers, designers, marketers, etc. I'll explain why the column is calledTrackbelow.Estimation— our time estimate for the task.Comments— any additional comments.

What is a track

In any project, you can always highlight several streams of tasks that would be nice (but not always possible) to perform all the time, for example, by taking one task per week. Otherwise, some parts of the project will degrade.

The simplest example from gamedev are tracks of development, game design, and art.

Parts of the project left unattended degrade

Suppose at some point we decide that, for example, we have done everything in game design, and developers still have a couple of months to code.

In that case, the game design (the real one implemented in the game, not the one in the heads of game designers) will degrade. It will not remain the same as it may seem.

Because the game model in the code will change (accumulate mistakes discrepancies), and the game design model in the documentation and in the heads of game designers will remain the same (old).

Therefore, in an ideal project with an unlimited budget, work is always going on for each track to ensure the project grows evenly, organically.

Note that tracks should not be confused with roles, positions, or competencies. Above, I gave an example of high-level tracks. Here is an example of more specialized tracks for web development:

- business logic development;

- improving/maintaining the project's controllability: metrics, logs, tests;

- improving/maintaining security level;

- improving/maintaining performance.

Business always usually has a habit of ignoring tasks from not-so-mandatory-and-noticeable tracks that do-not-bring-value-directly. For example, tasks to improve project controllability might get dismissed because "everything is fine now."

But the catch is that the debt in track grows like a snowball, snowflake by snowflake. If you don’t pay it off, eventually disaster strikes: all new features get postponed in favor of urgent fixes using quick-and-dirty solutions. This leads to significant disruptions in the business’s planning and, on top of that, to deep-rooted project degradation, which further derails planning over time, creating a vicious cycle.

That's why the project leader's goal is to keep all tracks active.

Accordingly, when starting to make a table, I decided to describe tasks by tracks, assuming that:

- the list of tracks will be determined as we go;

- at each stage on each track there will be some amount of work.

In fact, in our specific case, we could use roles instead of tracks. But if the project were larger, the tracks would be more diverse. For example, game design could be divided into tracks of level design, mechanics, and narrative.

Also, it is not guaranteed that as the product develops and the team grows, we will not want to increase the details of our plans.

How to break down epics into tasks

The most important thing is to have a sense of balance. With all our desire, we cannot know the complete list of interface elements, sounds, mechanics, and whatever else will be in the final game. Therefore, there is no point in making such a list.

Instead, we should define work in large chunks, focusing on common sense and our own experience.

If you have no experience, use common sense only. :-) Then, find an experienced friend and ask them to check your work. Doing the opposite (finding a person to do this work for you) is not recommended, as the person will leave, and you will be left with an artifact you do not understand.

Of course, it is okay to delegate task breakdown to a team member (who has signed up to work with you further). Even cooler is doing it together as a team. I don't have a team for now, so I did it myself.

In our strategy, we briefly defined the goals of each development stage and the expected result upon its completion.

For example, for the Alpha version:

- Goal:

Implement core game mechanics. - Expected result:

The PC game where you can play 1 game session and have some fun.

Knowing what game we are making, we can define what should be ready to complete this stage:

- Minimum game design description.

- Minimum user interface.

- Minimum game mechanics. In our case, it is a map, news channels, and events investigation.

- Some content.

We should complete these tasks as a team, but each epic contains a different amount of work for various specialists. Therefore, we should break them down into tracks.

Why is it not enough to have only epics

It may seem that it is enough to define only epics for the roadmap. The idea being, we work as a team, so first we all complete the first epic, then the second, and so on. But this is not the case.

Every game requires a unique amount of work in different areas. Somewhere, you need more graphics; somewhere, more game logic; somewhere, something else.

On the example of the game maps:

- There are games with wonderful maps but little logic behind them — they are just pictures.

- Some games have a complex map logic with scaling, different display modes, filters, buttons, and sliders.

- There are even games where the map is not displayed through graphics but through sound, and you will need a sound engineer, not an artist.

So, every track will have its own amount of work, and you should build a team that will pass through all tracks without downtime (wasting money). For example, if you have x work on art track, and 2*x work on development track, you should hire two developers per one artist.

That's why we need to know the amount of work per track.

But, as always, moderation is key. In some cases, it’s OK to leave out certain tracks.

For example, somewhere in the middle of filling out the roadmap, I saw that the amount of work for developers and game designers is significantly higher than for any other track. That means they will be the ones limiting the development speed, and for all other tracks I can hire only one person per each other track (taking in account the small expected size of the team). So I started to spend less time on writing down tasks for other tracks.

For example, we know that we need a map in our game — it is our epic Implement game map.

- What sort of map? Who knows. So, we create research tasks on two tracks:

game design— what should be on the map, how it should work;art— how it should look.

- Of course, we need to implement it, so we will create a task on the

developmenttrack. - It would be great to have a procedural map generation. But it is definitely not required for the Alpha version. So, we create additional epics and tasks for the Beta and Early Access stages.

Pay attention

We do not prescribe exactly what artist should draw (how many sketches, sprites, buttons) or what buttons and mechanics the developer should implement.

A detailed description of tasks will be required when actual production starts, when you will know your team's capabilities and plan the work in detail with all involved colleagues.

Besides the straightforward epics, there is an invisible work that is also mandatory. We cannot forget about it. Here are examples from my roadmap:

- Moving the game logic from the prototype to the real project. This is necessary because the prototype was developed using technologies that are convenient for prototyping (web), not for creating a game for Steam.

- Developing tools for game designers to speed up their work.

- Playtests at the end of each stage and game improvement based on their results.

- Development of QA approaches for content quality assessment. There will be procedural story generation in the game. Therefore, we need to somehow assess the generated stories' lower quality boundary. Are they diverse enough? Do they involve all NPCs? In other words, we need to protect ourselves from a random total failure when the generation algorithm starts to produce complete nonsense due to a bug in it. It is difficult for developers to notice such statistical phenomena because they cannot play full game sessions all day long (they have work to do).

- Worldbuilding for the game. A consistent, solid context will make it easier for game designers and artists to keep their work in sync.

- Validating and setting up diversity in the game. We are making a game about a modern metropolis, so we need to represent people of different races, views, and abilities.

- Tutorial.

- Creating the Newspedia (like Civilopedia in the Civilization series). The game will have many nuances, and we need to help players navigate them.

- Tasks on community building and working with it.

- Infrastructure for tracking game errors and metrics.

- Something fun for the Deluxe version, which we will sell a little more expensive.

- Modding support.

- Adaptation for people with disabilities.

- Wiki for the community.

Tasks estimation

Estimations are a complex and tricky question. The specific approach depends on your experience.

There are two main approaches:

- Estimation in story points — abstract units of complexity. For example, you state that the simplest task is worth one point and then estimate all other tasks proportionally to it. When everything is estimated, you convert points to working time at some rate.

- Estimation in ideal working time from the start.

Speak about work using working time, not calendar time

A calendar month has ±30 days but only ±20 working days. You pay salary for calendar months, but work moves in working months.

Therefore, the last operation in calculating the total development time will be converting working time to calendar time. In my case it is done in the Green table.

For my personal needs, I usually estimate work in "ideal working days" (when no one and nothing distracts the worker). I chose the same approach for the roadmap. But for joint estimation in a team, it is better to use story points.

Blue table

After we have described all the work, we can find out how much time each track will take at each stage of development. This will allow us to estimate the number of employees required for each track so that the work is done evenly.

For this, we group the Red table by the triple stage + epic + track and sum the working time in them.

| Stage | Track | Sum | Workers | Workdays | Work Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | development | 82 | 1.4 | 59 | 3 |

| Alpha | game design | 56 | 1.4 | 40 | 2 |

| Beta | development | 151 | 2.25 | 68 | 3.4 |

| Beta | game design | 85 | 2.25 | 38 | 1.9 |

| Early Access | development | 165 | 2.25 | 74 | 3.7 |

| Early Access | game design | 97 | 2.25 | 44 | 2.2 |

| Release | development | 150 | 2.25 | 67 | 3.4 |

| Release | game design | 114 | 2.25 | 51 | 2.6 |

My Blue table is already filtered

You may notice that there are only development and game design tracks in my Blue table. This does not mean that there were only these tracks initially! The table has already been filtered to display only the most significant tracks after it became clear that there was noticeably less work on the other tracks.ks.

Columns:

Stage— development stage.Track— track.Sum— total amount of work on the track at the stage in days.Workers— the number of employees that will be on the track at the stage. The fractional part is the share of my time that I can allocate to help. I will tell how to choose the number of employees for the tracks later.Workdays— the number of working days per person.Work Months— the number of working months that will take the track at the stage.

We convert the working time to (working) months because our estimates are very rough, and later, no one will need to know the "exact" number of days.

Green table

The Blue table gives us the lower (optimistic) estimate of the duration of each stage for our team (which we will talk about a bit later).

The goal of the Green table is to convert the optimistic estimate into a realistic one in a calendar time.

| Stage | Max | Forgotten Work % | Mistakes Fixing % | Learning % | Team Lubrication % | Vacations % | Expected Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | 3 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 5 |

| Beta | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 6 |

| Early Access | 3.7 | 0.3 | 0.075 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.08 | 6 |

| Release | 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.025 | 0 | 0.08 | 6 |

For this, we:

- Set the time of each stage equal to the duration of the longest track on it.

- Increase it by different smart coefficients.

- Round up because there is no limit to pessimism in software development.

Columns:

Stage— development stage.Max— the duration of the stage in months. It is equal to the duration of the longest track on the stage.Forgotten Work— our estimate of the share of work that we forgot to include in the stage. The coefficient increases with time because we see the first stages better than the last ones. Work on the last stages will significantly differ from the plan due to the accumulation of mistakes in our model of the game and the improvement of our understanding of it as the development progresses.Mistakes Fixing— the time we need to fix the errors/bugs we made. The coefficient decreases with time because we make fewer mistakes as we learn.Learning— training costs for the team. Expecting the team to know everything you need immediately after hiring is unrealistic. Our team should invest time in learning new tools, approaches, theories, etc.Team Lubrication— a penalty on the team's time to get used to each other. People need to learn to work with each other.Vacations— you didn't forget about vacations and illnesses, did you?0.08in the table is approximately1/12of a year.Expected Work— the rounded-up estimate of the calendar time for the stage.

The team's competence

Coefficients in the Green table depend on the team's competence, including yours.

The competence you expect from the team should be reflected in the salaries in the financial model.

In the end, we have 4 development phases, each lasting six months — a perfect plan for how to kill to productively spend two years of your life.

By the way, this is not counting DLCs. The development of DLCs is not included in the Roadmap because:

- The complexity of their development depends heavily on the quality of the game's architecture. Now it is unpredictable, like guessing on a goat's liver.

- The same applies to their content: there is no game yet — we don't know what to add to it.

- Since we’re aiming for long-term monetization through DLCs, we'll need to establish a DLC production pipeline after the initial release (features of which can be varied quite flexibly). This pipeline will be constrained from the top by marketing demands and community expectations, and from the bottom by architectural and team limitations. We’ll need to plan the features of each DLC in a way that fits within tight development timelines. It will be totally different planning.

The difference between developing the base game and DLCs

In a broad sense, we could put it this way.

While developing the base game, we can trade time (which investors will give us) for features (which we need to make for a complete game).

While developing DLCs, we will trade features (candidates for inclusion in the DLC) for time (which we will need to release the DLC on time).

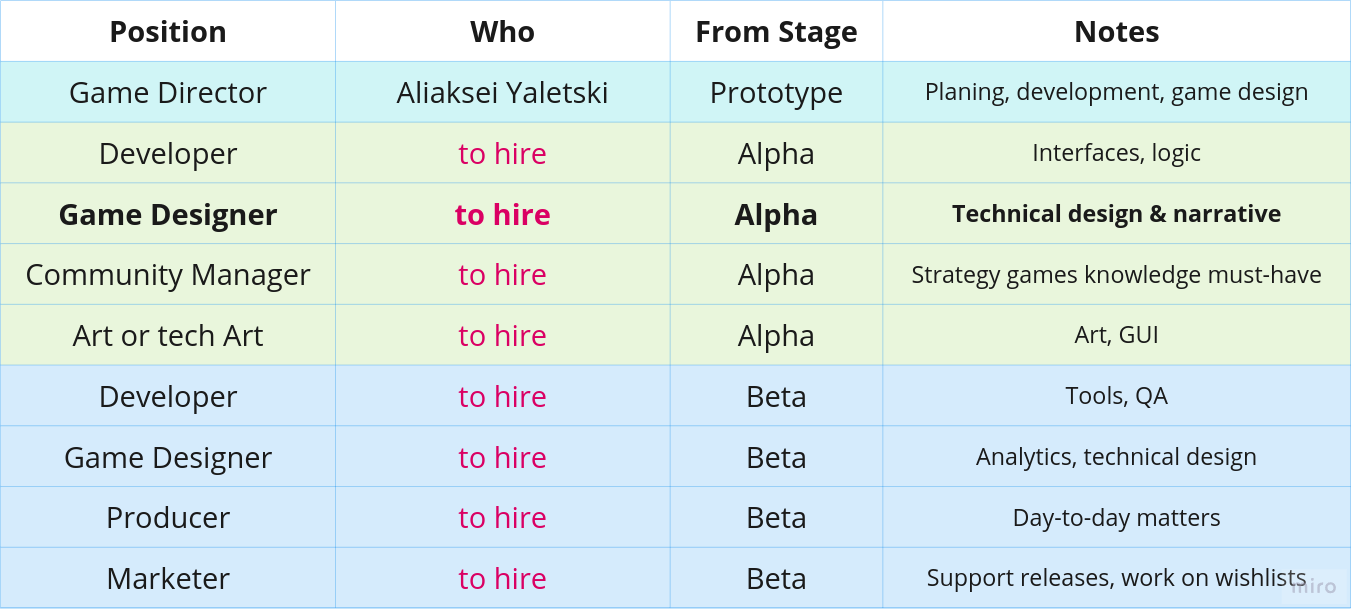

Composing the team

The final picture of the team we need to assemble. If you don’t crown yourself the director, who will?

So, in the Blue table, we need to write down the number of employees for each track at each stage of development.

When determining the number of employees, we should remember the following:

- On each stage, on each track, it is reasonable to have so many employees that all tracks are completed at approximately the same time.

- It is not mandatory to hire all employees at once. Firstly, new projects always start from the narrow front of work, when the presence of additional employees will only delay progress. Secondly, the fewer people you hire, the less money you need to ask. Especially if you are going to raise funds in rounds.

"Virtual" vs real employees

In the table, we operate with "virtual employees," not real ones.

While assembling a team, we will hire real, unique people, not interchangeable cogs. Therefore, as we hire, we should adjust the estimates in the Blue table to reflect the team's real capabilities. This will cause a recalculation of the terms and financial model.

Of course, we can look for a "pure developer," "pure game designer," and so on, but this will not be the best strategy, especially if you are a new indie developer. Looking for T-shaped employees is much more profitable.

- Firstly, it will be easier to establish communication in the team.

- Secondly, the team will be more flexible and autonomous and will require less management.

- Thirdly, since you are a noname team, such people are more likely to come to you. Narrow specialists usually go to large companies, where there is a narrow deep front of work for them.

I have no team yet, so I operated with "virtual employees" and just added my share of time to the estimates.

If you already have a team (or will have one), it’s wise to add a column in the Blue Table per each team member. This allows you to accurately track how much impact each person will have on each track. This approach also comes in handy if you hire a “star” who works like five people or an intern who may count as half of an employee.

Sometimes, it may be a bad idea

People are different. Per-person effectiveness estimation is a kind of rating. Some people will take it philosophically, while others may be deeply offended by it.

Detailed effort estimation may be a good idea from the planning and budgeting perspective. But it may be a bad idea from the perspective of team building and team spirit.

Take in mind your team specifics, before deciding to use this approach.

By following these logic, we may create an image of our future team:

- Two developers and two game designers to fill the main tracks.

- One key specialist for tracks with too many tasks for outsourcing.

- Hiring is in two stages: first, for the project kickoff, and then, for the steady development phase.

- Tasks and employee specializations are adjusted according to the requirements of each development stage. For example, we don’t need utilities or QA automation in the Alpha version, but they become essential for smooth development and achieving the desired quality later on. Therefore, we will hire a second developer by the start of the Beta version.

- We’ll hire a producer by the Beta stage since I can handle managing five skilled people part-time, but I’ll need help beyond that (I want to continue writing code and working on game design). Also, I don’t have experience managing outsourcing, so it would be great to delegate that responsibility.

Positioning — beacon games

.](https://tiendil.org/static/posts/world-builders-2023-business-plan-example/images/positioning.png)

Games that are similar in some ways to what we want to create. A more detailed 'raw' table can be found here.

Before we start developing a financial model, it would be useful to gather some information about the fate of similar projects.

- First, if there are no similar projects, it is a reason to think is the concept of our game is so unique that no one has ever thought of it, or is it so bad that no one has ever tried to implement it.

- Second, such a list will provide us a feedback on the expected amount of work and the team size. We can compare our calculations with real data.

- Third, it will allow us to estimate (using heuristics) some parameters for the business model.

I chose beacons based on genre and the significant player experience they provide. It is possible to philosophize about alternative approaches. For example, someone could dig up some Steam statistics or collect raw data and make some data science magic.

What data do we need:

- Development time.

- Team size.

- The price of the game at the release time.

- The number of copies sold.

- The estimated revenue.

Most of this data is private, and almost no one will give it to you. Especially the exact values.

But we don’t really need exact data (as if all our previous calculations were spot-on, yeah?), approximate information should be enough. In my case, I unexpectedly found it easily on Wikipedia and news sources.

Lifehack

I calculated the size of one of the teams by counting the number of faces on the photo from Reddit.

By the way, here is some advice. If you are going to make a game in the future, but not right now, start collecting links to interviews and press releases from developers. They will come in handy when you start planning.

In case Wikipedia is not enough, there are several Steam statistics aggregators, such as Steam Spy.

Marketing strategy

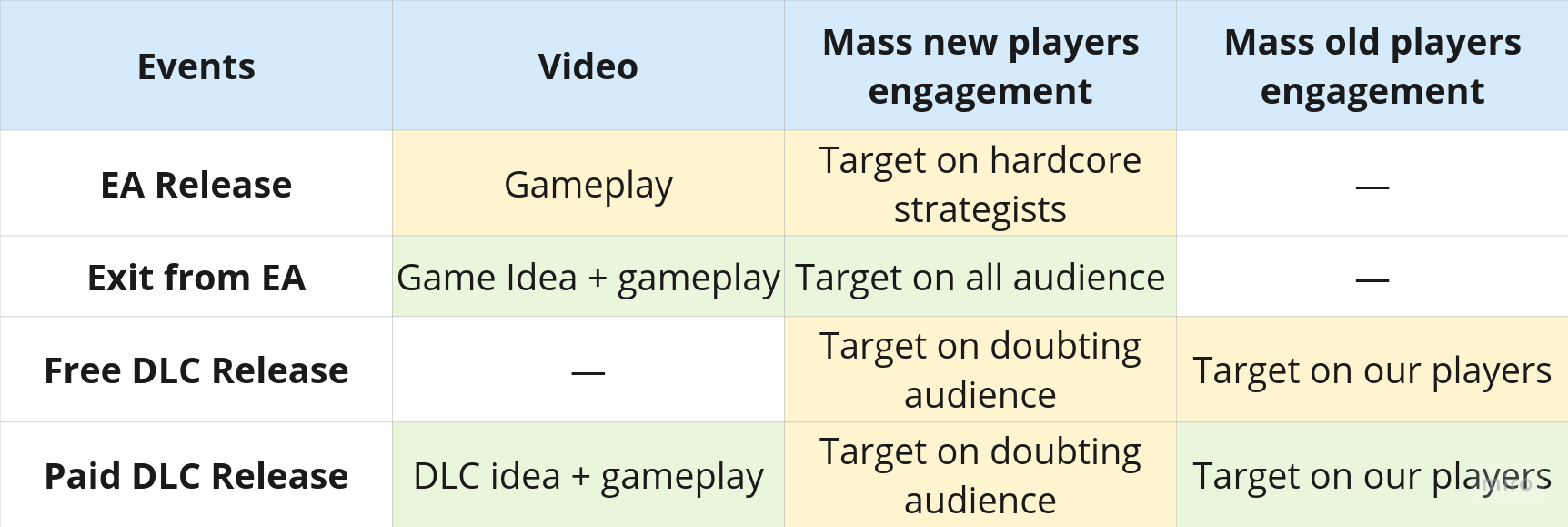

Expected marketing activities. Very large expenses are highlighted in green, just large in yellow. There are no small expenses in marketing.

One more important thing to do before preparing the financial model is to outline marketing activities. In our time marketing takes half of the development budget, if not more.

I'll skip the part with general ideas on building a community, finding players, and similar things. Firstly, there are a couple of related slides in the presentation. Secondly, it is a well-known and popular topic, there are plenty of materials on the internet. I even wrote a small essay [ru] about my experience. Plus, in my opinion, all these considerations are more about marketing philosophy (who and where to look for) than about actual expenses (how many players to look for and how much to pay for them). Here we are interested in how much to pay.

In the context of marketing, two things are important to us.

Firstly, key events for which we will prepare marketing activities:

- Early Access release.

- Exit from Early Access.

- Releasees of DLCs.

Secondly, the types of this activity, for us it is:

- Releasing a supporting video.

- Attracting new players.

- Returning old players.

Let's go back to strategy planning for a moment

For my game I decided to split DLCs into two types: paid and free, and alternate them.

Paid DLC should be cool. It takes longer to make, and most likely, the share of work for programmers will be greater than for game designers because it will contain new mechanics.

Therefore, between the release of paid DLCs, we can release simpler free ones. They will retain the interest of old players, enrich the base game, attract new players, and, of course, keep the game designers busy.

If you look at the chronology of events in the final financial model, you will see that players will see the release of a DLC every two months. But for developers, these will be cycles of four months. The development of two DLCs will start simultaneously. The free one will be prepared for two months, and the paid one for four, after which the team will move on to the next iteration.

An alternative to free DLCs could be updates to the base game. This may be even more convenient for attracting attention to the base game. However, for the purposes of this post, the difference is not significant.

In the rest, our focus should be visible from the table:

- We shoot gameplay videos for Early Access and spend "a little" on attracting hardcore strategy players to forge a core of our community.

- On the exit from Early Access, we shoot a cool video with the idea of the game and spend a lot of money on attracting a wide audience.

- On the release of free DLCs / base game updates, we return old players and spend a little on attracting new ones, focusing on the features of the DLC. For example, if the DLC is inspired by X-Files, we may launch a company aimed at fans of the series.

- On the release of paid DLCs, we shoot a video about the idea of the DLC and aim spendings at our community and a little at new players.

Financial model

Finally, we can get to the most interesting part — counting money.

You can find the spreadsheet with the calculations here.

It contains two sheets:

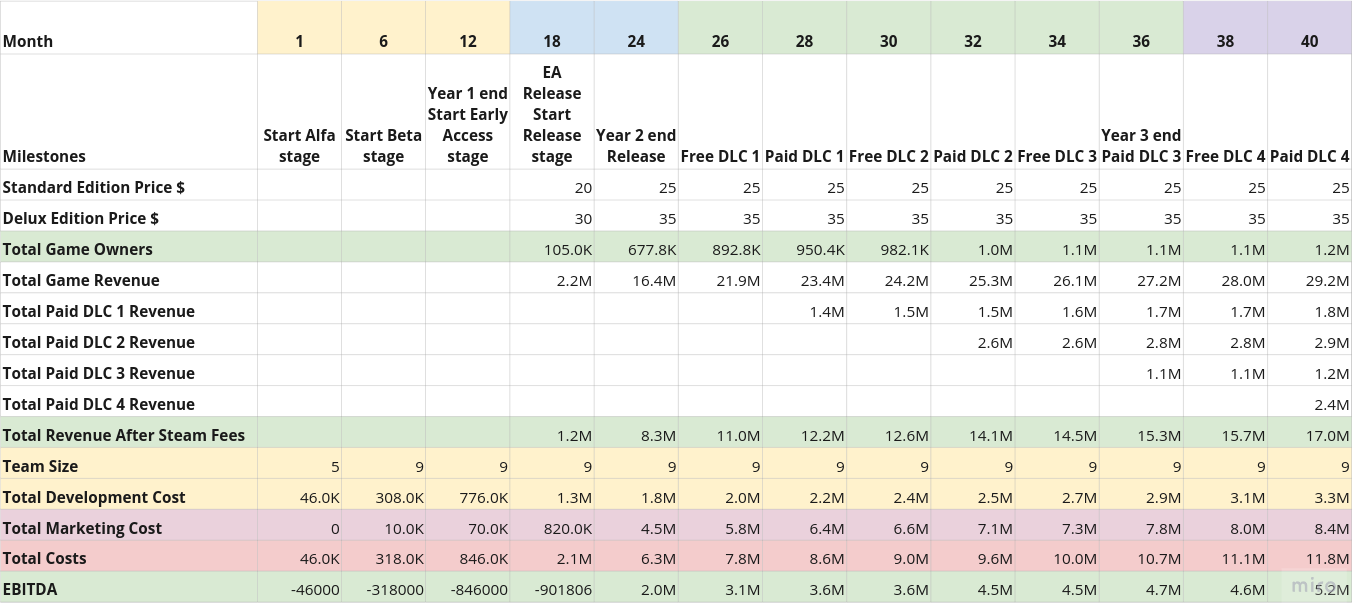

- A detailed monthly calculation — for us and for the convenience of modeling.

- A brief excerpt from the first sheet — a slice of the most important parameters at key points in development — for investors and a beautiful presentation.

The second sheet is built automatically based on the first one.

The model is built till the release of the fourth paid DLC, but it is calculated for a slightly longer period — until the end of the fourth year of development.

I will explain the first sheet. It contains 65 rows. The calculation goes from top to bottom, left to right, so I will just describe all the rows in order.

I won’t write down the formulas—you can find them in the original table—but I will describe the calculation logic if it’s not straightforward.

I’ve split the description into sections based on the relevance of the data. In the table, these sections are highlighted by different background colors.

So, let's go.

Look at the model through the eyes of an internal skeptic

A lot of input values in this model are taken not from statistics and reports but from the opinions of experts (e.g., school teachers), my common sense, and other not necessarily the most reliable sources.

Header

[1] Year — Color differentiation of the years of development for easy navigation.

[2] Month — The ordinal number of the month, also for navigation.

[3] Milestones — Important events in the life of the game. Each event usually changes the parameters of the financial model. For example, when starting the development of the Beta version, we increase the size of the team.

The events in the Milestones row are essential for investors

We select columns for the second sheet based on the presence of values in the Milestones row.

Base game sales

[4] Standard Edition Price $ — The price of the base game at the release. We choose it balancing our greed and the price of beacon games on their release.

[5] Deluxe Edition Price $ — The price of the deluxe version of the game. For players who want to spend a little more money on the game. We choose it a bit higher than the base game's price.

[6] Game Purchases / Month — The expected number of organic purchases per month. From the echoes of marketing, community building, and other activities.

No work — no profit

If you did nothing in marketing and community building before the releases, you will have 0 here.

[7] Game Purchases Boost— The number of game purchases we expect from our marketing efforts. This parameter is not calculated but set. The reasons for choosing this approach and its alternatives will be discussed later when we get to the marketing spending calculations.

These numbers will easily eat half of your budget, if not more

The more purchases, the more profit, but the bigger the marketing costs. Marketing costs go before profit, increasing the amount of money you ask from investors, thus reducing your share in the result.

While deciding on this number, consider:

- How much money you can get from the investors.

- How many players are in the chosen genre on the chosen platform. In my opinion, even 10% of the target audience is a booming success, aim at 1% or less.

Also note that your marketing will be tied to specific events. You will pour a lot of money into a particular month and then maintain some minimal activity to pick up the tail.

[8] Game Purchases Boost Tail — Players who will purchase the game as a tail/echo of your marketing activities. Calculated as 1/3 of the effectiveness of marketing in the previous month. I took 1/3 by eye from SteamSpy charts (how quickly the audience growth rate decreases).

[9] Game Purchases / Month — The total number of purchases of the base game per month.

[10] Total Game Owners — How many purchases will be made over time, including this month.

[11] Deluxe Edition Purchases % — The share of purchases of the deluxe version of the game. I estimated it as a modest 5%.

[12] Standard Edition Purchases — The number of purchases of the base game per month.

[13] Deluxe Edition Purchases — The number of purchases of the deluxe version of the game per month.

[14] Standard Edition Revenue — How much players will pay for the base version per month.

[15] Deluxe Edition Revenue — How much players will pay for the deluxe version per month.

[16] Game Revenue— How much players will pay for both versions per month.

[17] Total Game Revenue — How much players will pay for both versions over time, including this month.

DLC sales

All paid DLCs are described using the same logic, so I will only describe the rows of the first DLC.

[18] Paid DLC 1 Convertion Rate — Our estimate of the share of base game owners who will buy the DLC. I took the estimate by googling the news, but there is not much information. 30% conversion is an ambitious goal.

[19] Paid DLC 1 Purchases — The number of players who will buy the DLC per month. There is a slightly confusing formula, but its essence is to count old and new players coming each month and not count people twice.

[20] Paid DLC 1 Price — The price of the DLC. We balance between greed, industrial standards, and our idea of the volume of the DLC. To determine the acceptable price range, I just looked at the prices of Paradox DLCs. Plus, the first DLC is expected to be smaller because it will be the first, and it will take some time to solve inevitable technical problems. Therefore, the price should be lower.

[21] Paid DLC 1 Revenue — The expected revenue from the sale of the DLC per month.

[22] Total Paid DLC 1 Revenue — The expected revenue from the sale of the DLC over time, including this month.

Parameters of the following DLCs will differ

- By the date of the release;

- By the price. I see it reasonable to vary the price of DLCs cyclically.

- By the expected conversion rate. I have no data, but I expect it to reduce with time. In my case, I decrease it from

30%to20%over time.

Calculating the money we'll receive from Steam

Of course, not all money from the players will end on our bank account. In this section, we estimate how much money we'll actually see.

[38] Raw Gross Revenue — The total revenue from the sale of the base game and all DLCs per month.

[39] Expected Discounts Loss — The expected "losses" from discounts on Steam.

How we account for discounts

There may be two approaches to calculating the effects of discounts.

- We consider purchases on discounts as a separate type of purchase, like DLCs. In theory, this will give more accurate results, especially if you have access to statistics. The downside here will be a significant increase in the size of the table.

- We turn to expert opinion, which says that we will "lose"

X%of potential revenue because of discounts. Since we have no access to secret statistics, but we have school experts, this is our way.

I write "lose" in quotes because it is not an actual loss. It is more of an acquisition of new players who would only buy the game at a partial price. However, we will use the term "lose" because it is more suitable for calculation logic.

So, as I understand, in the long run on discounts the game can "lose" up to 50% of the potential revenue. But we will not have such large discounts right away. Therefore, I estimated the growth of losses on discounts from 20% to 50% with a half-year step.

[40] Raw Gross Revenue - Discounts — Our revenue after accounting for discounts.

[41] Steam Fees — The standard 30% Steam fee.

[42] Revenue After Steam Fees — Our revenue after the Steam fee.

[43] Total Revenue After Steam Fees — Our ongoing revenue after all losses and fees, including this month.

Spends on development

The part of the model for which we spent so much time calculating the roadmap and team composition.

[44] Team Size — The number of people in the team.

Costs of hiring

Depending on the availability of a team, your plans, agreements with investors, and other nuances, it may be a good idea to include the costs of hiring employees in the model. It can be quite expensive.

In my case, there is some uncertainty about how the team will be assembled (there are outsourcing options, for example), and there is an option when I assemble people on my own.

[45] Average Gross Salary $ — The average salary of a team member.

Should we specify salaries per position?

I do not see any reason to do this.

Not always, but often, it’s easier to adapt the roadmap and even the product concept to the team, rather than build a team around the product. For example, when I worked on The Tale, I changed the style of the game from humorous to serious because I met game designers who were great at serious texts. In the case of large projects, this is not so relevant but still worth considering.

Oversimplifying, you do not know who you will hire. A cool, motivated specialist can turn your entire development in a wholly new and cooler direction just because of their experience and unique vision. Dismissing such an opportunity is not worth it.

[46] Sallary Indexation — Salary indexation. I think almost no one includes this but in vain. In my opinion, this should be an obligatory element of the agreement today. So to say, an aspect of work ethics.

[47] Final Sallary — The final average salary with indexation.

[48] Team Cost — The total cost of the team per month.

In reality, the team costs will be higher.

Maintaining an organization leads to many indirect costs: office, accountant, lawyer, etc.

I have not included these costs in the model. It is not clear for which country to count them, nor for which configuration of the team (remote, office, mixed, b2b or hiring, etc.). At the time of creating the model, it was not clear whether a separate company would be created or not.

It is a drawback of this financial model. But compared to the size of the marketing costs, the "forgotten" amount will be small.

Ideally, we should have pulled up some statistics, consulted experts, and stated that “on average, maintaining company operations costs X% of the payroll budget.”

[49] Average Outsource Staff — The number of outsourcers we will work with. My "expert" estimate: something will always be outsourced, but it is unclear to what extent, most likely in a small one, so 1.

[50] Average Outsource Cost — The expected cost of one outsourcer per month. The logic is the same as with the average team salary.

[51] Outsourcing Cost — The total cost of outsourcing per month.

[52] Development Cost— The total cost of all development per month.

[53] Total Development Cost — The overall cost of all development since the beginning of time, including this month.

Calculating marketing

Let’s take a break from the table and think about how we’re going to calculate the marketing budget.

Estimating the effect of marketing activities through the number of wishlists

It's currently trendy to calculate conversion rates from Steam wishlists to actual purchases. And then apply them somehow to the future games.

I see here a few significant problems:

- By operating with wishlists, we complicate our model. We create two uncertain stages: collecting wishlists and converting them into purchases. The behavior of our product, Steam, and players at each of these stages is weakly predictable, aka random. In my opinion, a model with two "random" parameters will give worse results than a model with a single "random" parameter that we'll use.

- Steam and gamedev in general are very dynamic environments. Any Steam update can easily shake complex models. For example, they recently improved the support of game demos, as a result, the logic of promoting games has changed, and the

New & Trendingsection is now full of demos instead of complete games. Accordingly, if you had data on the cost of wishlists in previous years, they may be no longer relevant. - I've not found reliable statements about the "cost of adding a game to the wishlist", and the conversion rates from wishlists to purchases can vary by a factor of 1.5-2. Moreover, the estimates will differ for different genres, styles, and sizes of games. There are not so many statistics for strategies, rather not at all, because there are not so many strategies.

- Based on what I've seen on the internet, all the fuss with wishlists looks like another hype about another silver bullet that will solve everything.

In our model, we will choose a simpler and more reliable approach — we will estimate the cost of attracting a single player to purchase the game, CPI — Cost Per Install. Don't confuse it with Cost Per Impression, in this post we will only talk about installs.

CPI for Steam is as vague as conversions to wishlists and from them, but:

- It is a single parameter, not two. There is less effect of error accumulation and no temptation to adjust the parameters to each other.

CPIis easier to estimate. It is enough to know the marketing budget and the total number of game sales. We got this information when we were looking for beacon games.CPIis a global inertial phenomenon, it is less inclined to change unexpectedly, usuallyit only increasesfollows long global trends.- An estimate of

CPImay be more accurate than conversions to/from wishlists, because it is directly and rigidly limited by the market: budgets, people's willingness to engage in advertising, etc. Companies that do bad marketing leave the market. If we use data from successful products, we should get a relatively realistic estimation ofCPI.

CPI for the base game we will estimate simply:

- The marketing budget for beacon games is taken as half of their revenue.

- By dividing the marketing budget by the estimated number of purchases, we get

CPI.

Out CPI (for the base game) is set approximately as an average between beacon games. Additionally, I want to note that we have set lower sales than beacon games have, so our CPI may be slightly lower. CPI grows as the target audience is covered, as it becomes more difficult to find new players.

Marketing costs

So, let's return to the biggest are of our spendings. According to the final calculations of our model, by the release, we will spend 2.5 times more on marketing than on development :-D

I may have underestimated the number of marketers on the team

Given the size of the budgets, there may be more marketers required. On the other hand, we can outsource all marketing and limit ourselves to the lead of marketing in our team.

[54] Marketing Ongoing Cost — An estimated cost of minimal permanent monthly activity for "light" PR of the game to stay on the radars.

[55] Marketing Videos Cost — The expected cost of developing videos for concrete events (releases). The cost of a video minute can be relatively easily Googled. Or you can even ask for price lists from companies that do this.

[56] Marketing New User Cost — The expected cost of attracting new players — CPI.

[57] Marketing Old User Cost — The expected cost of attracting our players to purchase DLCs.

Here is great uncertainty

This is our crucial constant, as we have chosen to monetize through the sale of DLCs.

The problem with it is that, unlike CPI for the base game, it is unclear how to estimate CPI for DLC. Fluctuations in this value strongly affect the model.

Our model uses an estimate based on my conversation with the school experts.

Also, regarding the conversion of wishlists, I believe estimating them for DLCs is even harder than CPI.

[58] Marketing Performance on New Users (Game) — The cost of attracting new players to the game, per month.

Direction of calculations

We can calculate marketing in two directions:

- We ask investors for

X$per month for marketing, based onCPIwe will attractYplayers. - We want to attract

Yplayers, so based onCPIwe will ask investors forX$per month for marketing.

I chose the second option, but rather for personal convenience than because it is more correct. Look at your preferences, what you want to get from the final model, and what levers you want to twist.

For me, the lever to change the number of sales (game owners) looks more natural.

[59] Marketing Performance on Old Users (DLC)— The cost of attracting our players to purchase DLCs, per month.

[60] Marketing Month Cost — The total cost of marketing per month.

[61] Total Marketing Cost — The overall cost of marketing since the beginning of time, including this month.

Expected profits

The most important part of our table — the result of all our work, research, and calculations.

[62] Month Costs — All costs per month.

[63] Total Costs — The overall costs since the beginning of time, including this month.

[64] Month Gross Revenue — Our revenue per month, after all incomes and costs.

[65] EBITDA— EBITDA as it is — our money before removing indirect costs (taxes, amortization, interest, etc.). This parameter is essential for investors.

What to do after the financial model is finished

After you enter the last formula, stretch the columns for the required number of months, color everything, you will look at the final numbers and see that there is some unprofitable crap. Or, conversely, very suspiciously profitable.

It means the beginning of the most exciting stage of setting up the model when you twist a bunch of levers (constants in the table), play with the volume of work, and tune the size of the team to get a picture that will be convincing for you, your team, and investors.

Have Fun!

How much time did it take to develop the business plan

Instead of a conclusion, I will provide statistics on the time these documents took from me.

Of course, this is an approximate time, because I did not do this work full-time.

- Short strategy of the company — You develop strategy not at some specific moment, but all the time while working on ideas, concepts, presentations and so on. Later you just write down the information that already sits in your head.

- Table of beacon games — ±2 days. I spent a lot of time trying to understand what to search and how to search. When I figured it out, it went quickly.

- Team composition — less than a day. The basic composition should be well visible from the roadmap.

- Roadmap — ±2 days.

- Outlines of marketing strategy — Here are the same considerations as with the company strategy.

- Financial model — ±3 days, the idea of calculations changed several times. If you take a ready-made model, it will be much faster.

That’s all for now. Thank you for your time, and best of luck in game development!

This post is a part of series

- Previous post: Simulating public opinion in a game

- First post: Cleaning up the results of the strategy players survey

Read next

- Dungeon generation — from simple to complex

- Generation of non-linear quests

- The harsh reality of gamedev — the real profit of a successful project

- Pricing model at the start of Feeds Fun monetization

- Concept document for a space exploration MMO

- Two years of writing RFCs — statistics

- Vantage on management: Hypothesis testing loop

- «Slay The Princess» — combinatorial narrative

- Feeds Fun: marketing test — or how I blew 650 euros

- Key principles on in-game virtual currencies in the EU