Notes on backend metrics in 2024 en ru

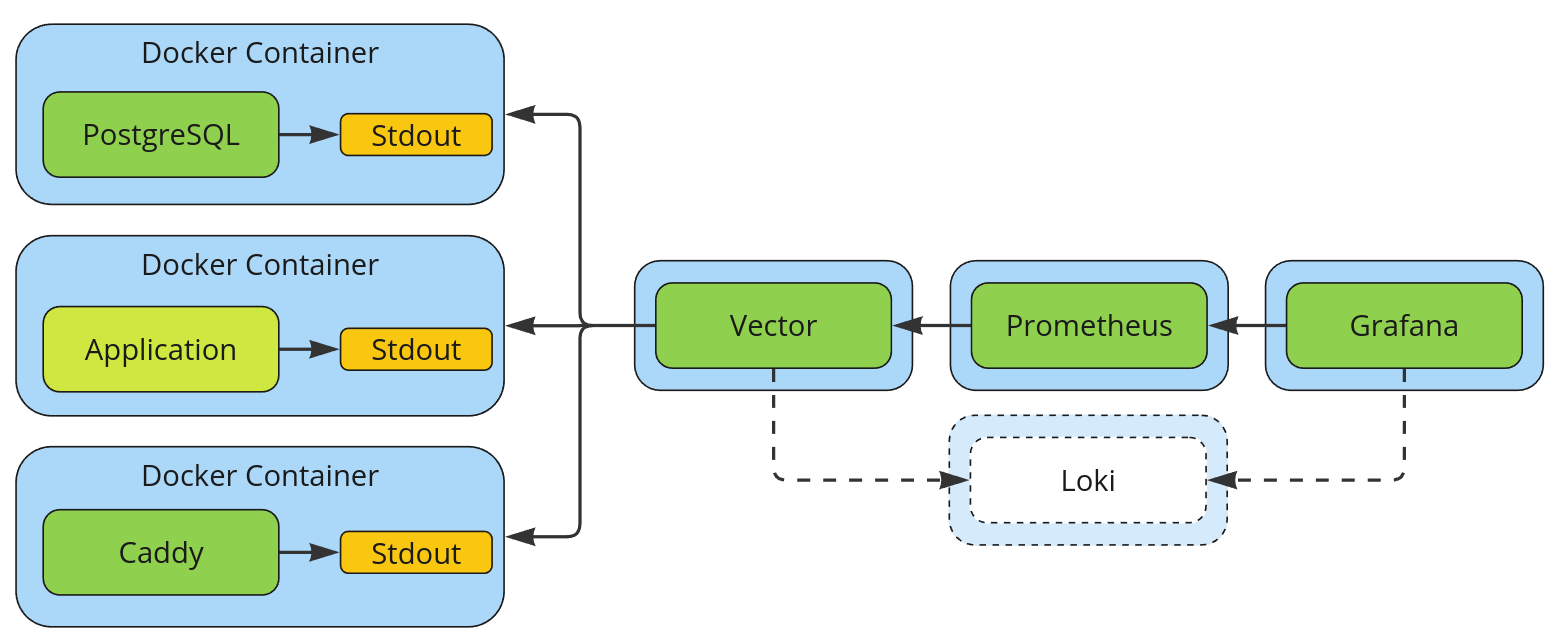

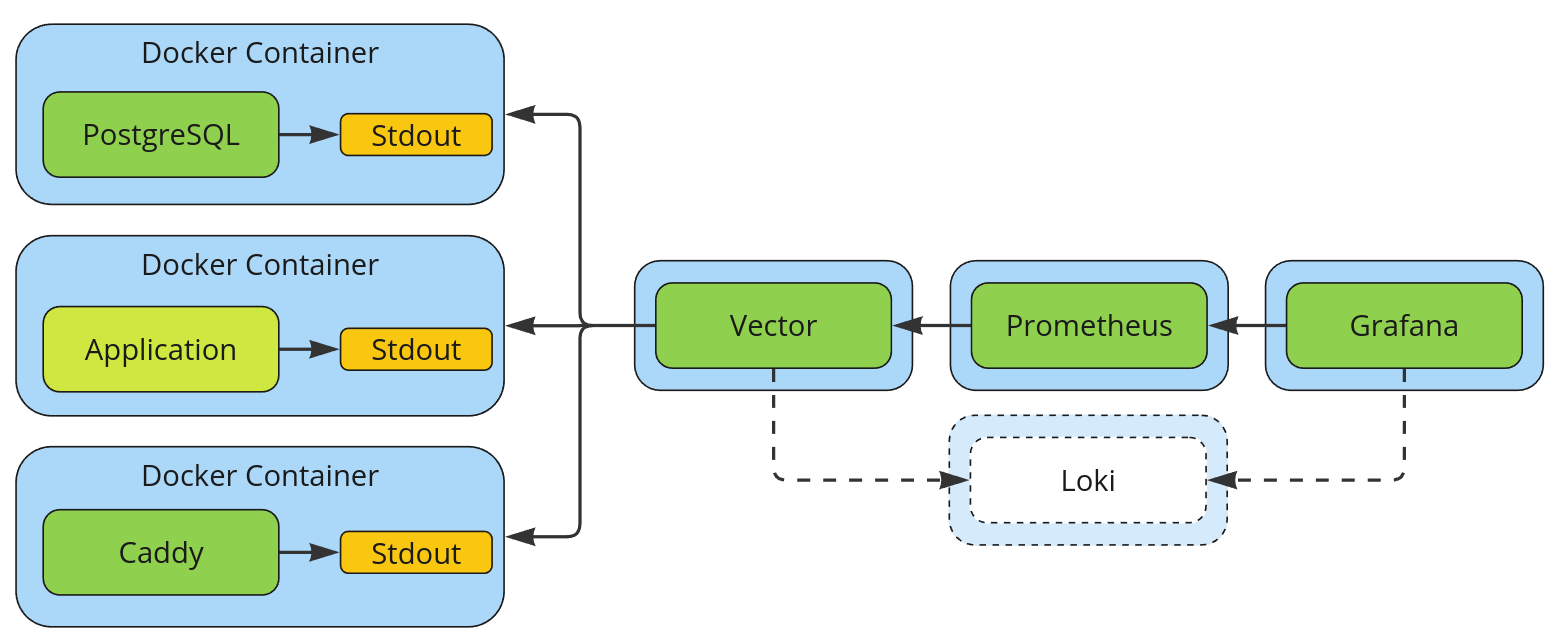

How metrics are collected in Feeds Fun. Loki is added to demonstrate the possible next step in infrastructure development.

Once in 2-3 years, I start a new project and have to "relearn" how this time to collect and visualize metrics. It is not a single technological thing that changes over time, but it is guaranteed to change.

I sent metrics via UDP [ru] to Graphite (in 2024, a post from 2015 looks funny), used SaaS solutions like Datadog and New Relic, aggregated metrics in the application for Prometheus, and wrote metrics as logs for AWS CloudWatch.

And there were always nuances:

- The features of the project technologies and architecture impose sudden restrictions.

- Technical requirements for metrics completeness, correctness, and accuracy collide with business constraints on the cost of maintaining infrastructure.

- Specialized databases for storing time series emerge, with which backend developers rarely deal directly.

- Not to mention the ideology and personal preferences of colleagues.

Therefore, there is no single ideal way to collect metrics. Moreover, the variety of approaches, together with the rapid evolution of the entire field, has produced a vast number of open-source bricks that can be used to build any Frankenstein.

So, when the time came to implement metrics in Feeds Fun, I spent a few days updating my knowledge and organizing my thoughts.

In this essay, I will share some of my thoughts on the metrics as a whole and the solution I have chosen for myself. Not in the form of a tutorial but in the form of theses on topics I am passionate about.

Metrics are the basic tool for managing the technical state of a project at the operational, tactical, and strategic levels

Metrics are literally a developer's eyes. Without them, it is impossible to see both the project's current technical situation and its long-term trends.

If we take the classic loop from systems engineering (and other memeplexes [ru]):

- data collection;

- analysis;

- synthesis/decision-making;

- implementation of the solution;

then metrics are the first step in the loop (and part of the second). Without them, closing the feedback loop for effective project management is impossible.

Speaking of planning levels, metrics help:

- At the operational level, to deal with force majeure situations faster.

- At the tactical level, to eliminate negative trends (like degradation of performance due to data growth) before they hit.

- At the strategic level, to plan expensive changes in architecture and infrastructure. For example, by justifying the need for database sharding or the introduction of queues.

However, that does not mean that the first commit should be the implementation of metrics — everything is good in moderation.

When developing a prototype and even when delivering the first versions to production, you can rely on your experience, intuition, periodic manual checks of the system state, and the discipline and competence of the team. After all, poorly working business logic without metrics is usually better than non-implemented business logic with excellent metrics :-D

The general idea is that the greater the impact of risks, the more metrics you need.

You need to monitor metrics visually/manually

Metrics are needed not only to look at them during incidents or long-term planning; rather not only to provide data for triggers.

Metrics show us the dynamics of the project — its internal life.

The habit of periodically looking at metrics with your own eyes initiates a feedback loop for refining your mental model [ru] of the project. An accurate mental model is the key to your effective work and the speed and quality of decisions you make.

You don't know what metrics you will need

There are basic metrics that everyone, or almost everyone, needs. For example, percentiles of response times for requests, requests per second, number of errors, number and percentiles of requests for each of the API endpoints, sizes of databases, tables, indexes, and so on.

However, as expected, basic metrics only allow you to react to basic/common issues. This is already a lot, but each project, as is its development path, is unique. Therefore, besides common issues, you will have ones unique to only your situation that will require unique metrics.

For example, at my last job, we implemented distributed transactions for processing payments using orchestration-based saga in the form of FSM. At some point, we needed to see the dynamics of the FSM distribution by their states, which was very helpful.

Unfortunately, in most cases, newly added metrics will not have a history. And the history of changes is what makes metrics really useful. Suppose you encounter an issue and see it in the metrics. In that case, you will want to know not only their current values but also their dynamics: the direction of changes, cyclicity, seasonality, and so on.

Therefore, it is reasonable to follow the following heuristics:

- More metrics are better than fewer.

- If you have come up with a metric that is easy to add, add it.

- If you have a critical component in the system, turn on the paranoia mode and cover it with metrics from top to bottom.

This is why I dislike SaaS solutions that charge for the number of unique metrics. Especially with the difinition of uniqueness as a combination of the metric name with all possible combinations of its tags/labels. Such restrictions force developers to spend too much time on designing metrics instead of developing the application.

Metrics history should be long

In my practice, I often encountered statements like "Two weeks of metrics history is enough". The argument is that any significant problems will emerge in two weeks. And if there were no problems, then a longer history is not required—let's save money.

This is fundamentally wrong for the following reasons.

People make mistakes [ru]: they mess up, forget things, get distracted, work in crunch mode, go on vacations. The fact that no one noticed an issue for two weeks doesn’t imply it’s absent or unimportant.

Our systems are not perfect: especially auxiliary ones like monitoring. Monitoring is often discussed in terms of an "ideal system we'll build someday" — one that includes every possible metric and anomaly detector. But no one has ever had a perfect monitoring system. In most cases, it’s developed on a residual basis, as it only brings direct value to the technical team.

A lot of processes in life are non-linear: an effect of an issue can grow exponentially. For example, a request’s duration could quietly increase by 1% daily over months, only to jump 20-fold in a week. With a short history, we won’t spot the trend in time (the slope over a short interval will be barely noticeable) nor quickly identify the trend's starting point.

An application code should not be aware about your Service Level Agreements

Your application's goal is to execute its business logic and provide clear, accurate measurements of its state—to be a source of truth. How to process those measurements and act on them is a separate question that external tools should address.

Tasks of your application should not include calculating percentiles, reducing metrics accuracy, aggregating them, and so on.

First, it does not relate to business logic and, therefore, does not benefit users directly.

Second, it complicates the application, making it harder to modify and maintain. Not critically, but still complicates.

Third, it complicates and slows down changes to metrics. For example, if you use Prometheus and want to change histogram buckets:

- For each histogram change, you must update the application configs on production at best. At worst, you will have to update its code, which means making a full release. And let's be honest: most of us will release it because we are too lazy to move metric parameters to configs.

- If you suddenly need to split metrics by histogram types (e.g., one for fast operations, another for slow ones), you will have to change the application code, and these may not be trivial changes.

Fourth, if you have several versions on production (a/b tests, slow release rollout, demo servers, etc.), you may end up with a mess of incompatible measurements that will complicate analysis.

Fifth, an application cannot act on metrics, so it should not try to process them in any way. Oversimplifying, it cannot say whether it needs to scale application servers horizontally or scale the database server vertically. Not to mention the scaling initiation — this should be done by systems above the application.

This is why I don't like Prometheus's approach to collecting pre-aggregated metrics — I just don't understand how to live with it.

An application should only push metrics (instantaneously)

An application should not store metrics in the belief that something will collect them later.

Firstly, "someone" may not collect them for a vast number of reasons. For example, because the application crashed a second before, let's say, Prometheus reached it.

Secondly, your collector will never reach everything, no matter how hard you try. There are always autonomous scripts that also need to be measured. Sometimes, there may be issues with system boundaries and security perimeters. So you will still have to implement push logic for special cases, which means doing the work twice, complicating the infrastructure.

That's another reason why I don't like Prometheus's pull approach.

Metrics and logs are one and the same

Both are telemetry.

A metric can be a log entry, and a log entry can be interpreted as a metric.

Therefore, there is no point in separating them in the application. Trying to work with metrics and logs differently complicates the architecture, infrastructure, and your life in general.

Given the current (strictly positive) trend towards structured logs (when each log entry has a strict format, usually JSON), it makes sense just to write everything as logs to stdout.

In such a case, there is little left of the metrics on the application side.

Firstly, some kind of wrapper function for logging, like

def measure(event: str, value: int | float):

logger.info(event, m_kind="measure", m_value=value)

Secondly, some mechanism for setting tags/labels for all log entries, if you plan to use tags.

Implementation of metrics on the Feeds Fun backend

For example, here is what I came up with:

- I added a

measuremethod directly to the logger class, so I can register measurements wherever there is a logger. - For tags, I use a context processor that sets contextvars in combination with a separate log processor from structlog, which merges tags into each log entry.

- All logs are written to stdout.

It looks like this (full source):

LabelValue = int | str | None

class MeasuringBoundLoggerMixin:

def measure(self,

event: str,

value: float | int,

**labels: LabelValue) -> Any:

if not labels:

return self.info(event, m_kind="measure", m_value=value)

with bound_measure_labels(**labels):

return self.info(event, m_kind="measure", m_value=value)

@contextlib.contextmanager

def measure_block_time(self,

event: str,

**labels: LabelValue) -> Iterator[dict[str, LabelValue]]:

started_at = time.monotonic()

extra_labels: dict[str, LabelValue] = {}

with bound_measure_labels(**labels):

try:

yield extra_labels

finally:

self.measure(event,

time.monotonic() - started_at,

**extra_labels)

@contextlib.contextmanager

def bound_measure_labels(**labels: LabelValue) -> Iterator[None]:

if not labels:

yield

return

bound_vars = structlog_contextvars.get_contextvars()

if "m_labels" in bound_vars:

if labels.keys() & bound_vars["m_labels"].keys():

raise errors.DuplicatedMeasureLabels()

new_labels = copy.copy(bound_vars["m_labels"])

else:

new_labels = {}

new_labels.update(labels)

with structlog_contextvars.bound_contextvars(m_labels=new_labels):

yield

Processing metrics on the Feeds Fun backend

You could see what happens to metrics after they are written to the log on the image at the beginning of the post. I'll duplicate it here, just in case.

How metrics are collected in Feeds Fun. Loki is added to demonstrate the possible next step in infrastructure development.

- The application and all utilities run in Docker containers. More specifically, in Docker Swarm, but that's not important.

- Vector is configured to collect logs from Docker and do various things with them:

- Part of the logs is transformed into metrics and aggregated according to Prometheus rules.

- All logs are sent to a log storage service like Loki, but this will be implemented later; I haven't spent time on this part yet.

- Prometheus goes to a single point for all metrics.

- Grafana draws dashboards based on metrics from Prometheus.

Most manipulations with metrics: changing the structure of the buckets in histograms, deriving new metrics, editing labels, ignoring metrics, etc. I can do by changing the Vector configs without affecting the work of the application.

It is convenient that the definition of log sources in Vector can be configured quite flexibly. For example, in my case, application containers are detected by the prefix of the container image name. So, no matter what new I run on the backend (services, cron tasks, etc), as long as it has the same base image, its logs and metrics will be tracked automatically.

It is also convenient that when deploying new servers and services, I will only need to configure data streams in Vector (or between Vector instances); no changes in Prometheus configuration are required.

Read next

- Fun case of speeding up data retrieval from PostgreSQL with Psycopg

- Prompt engineering: building prompts from business cases

- Two years of writing RFCs — statistics

- Dungeon generation — from simple to complex

- World Builders 2023: Preferences of strategy players

- Generation of non-linear quests

- World Builders 2023: Preparing a business plan for a game on Steam

- Pricing model at the start of Feeds Fun monetization

- Feeds Fun: marketing test — or how I blew 650 euros

- LLM agents are still unfit for real-world tasks